HORSEPLAY

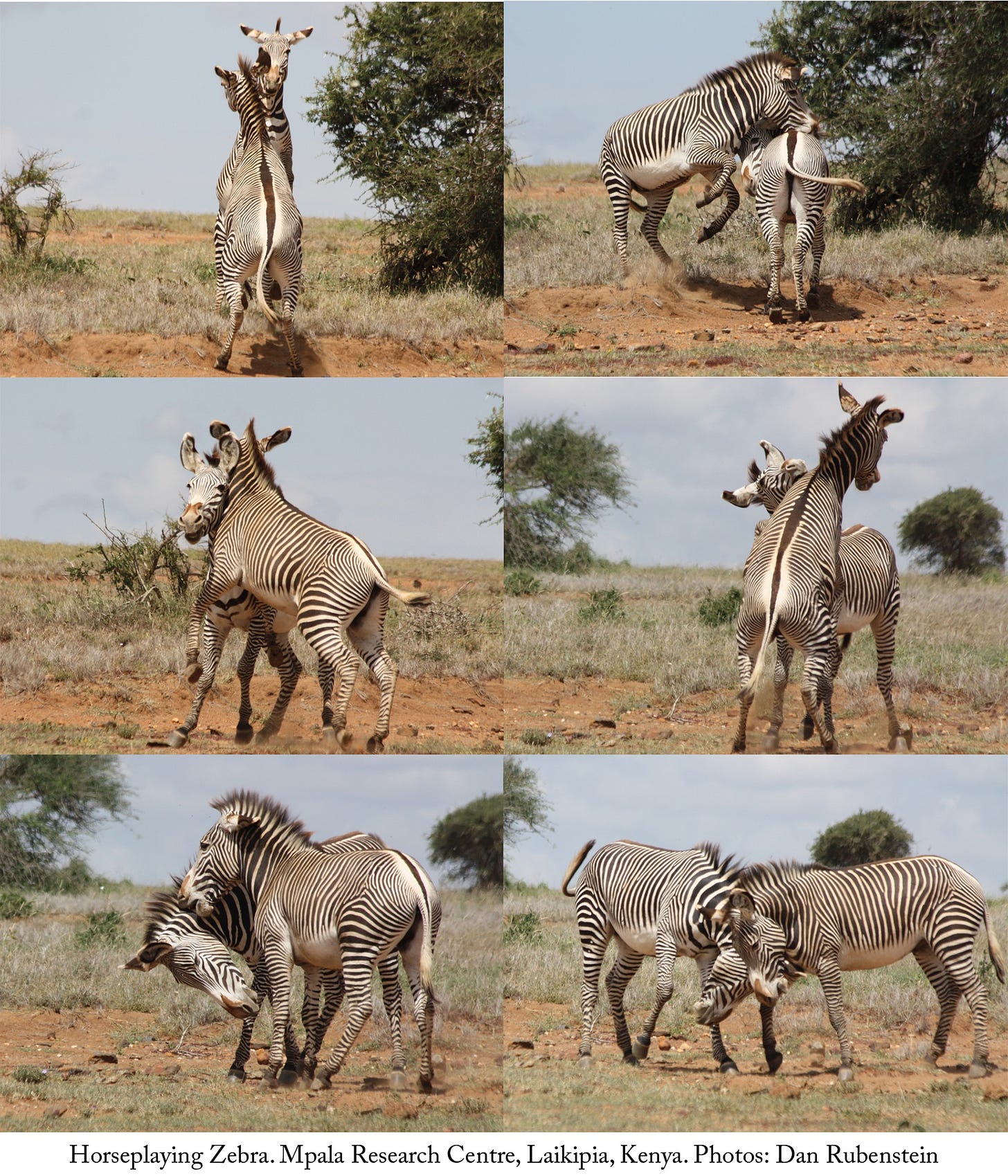

The frolicking play of horses and zebras might look wild and fun, but research has shown that it is neither frivolous nor a luxury of youth or good times - writes Professor Daniel Rubenstein.

Many animals play, but apart from the play-acting possum, I’m not sure of any other that have a type of play named after them. Young horses and their evolutionary kin—zebras and wild asses—often play wildly, frolicking around, jumping in the air, twisting and turning and generally racing about. And when they do so with playmates, other youngsters or sometimes even adults, these actions often appear mischievous as well; taunting, chasing, nipping, snapping and at times rearing and even striking at each other. Wild and mischievous as it may appear, this form of rowdy roughhousing rarely gets out of hand; the horseplay of horses appears genuinely playful and remarkably fair. Why do horses, and in fact all the equids, even those facing extreme levels of predation, engage in this extreme form of play? And when they do, how is it moderated to remain playful rather than becoming harmful?

Play among animals generally comes in three forms—locomotor, object and social. Within hours of birth, horses are up and about. While unsteady at first, after a few days they often start running about, changing speeds, twisting and turning, jumping and kicking. Sometimes jumps shift a foal’s weight onto its front legs, enabling it to kick out its hind legs. At other times, foals rear on hind legs letting them box at the air with front legs extended. Such movements are often spontaneous; at other times they are triggered by the actions of others. Given the wide-eye looks, exaggerated head shaking and ear flopping that foals show when loco motoring, young horses seem to be relaxed and actively enjoying gamboling and frolicking about. As foals mature and stray from their mothers, they often begin toying with novel objects: sticks, stones and the like. Exaggerated body movements highlight the intensity of such object play, but exuberant repeated approaches and retreats suggest pleasure in mastering a manipulative task. Even free-ranging feral or truly wild horses will grab and wrestle with tall clumps or grass, shake shrubs or kick rocks about. Probing and manipulating objects tends to increase as foals explore the world around them.

While such examples of locomotor or object play may seem aimless, it is highly likely that such behavior is adaptive and will ultimately contribute to the adult animal’s reproductive success. It’s as if such play is evolutionarily purposeful. Locomotor play certainly will increase stamina and dexterity, both traits that will be called upon when fleeing from danger. And object play will increase cognitive skills which will facilitate moving freely through complex environments and when acquiring difficult to manipulate food items.

Our studies on feral horses on a barrier island off the coast of North Carolina have shown that foals generally show a peak in locomotor play during the first few weeks of life. After decades of observations on juveniles dying of natural causes, those not surviving to one year of age—the age where they can forage completely on their own—showed lower levels of locomotor play than did survivors during the first year of life. They also showed lower levels of social contact and mock fighting with peers and adults, thus suggesting that the third form of play—social play—is also adaptive. By developing synaptic connections in the brain that tie motor skills associated with locomotion, object manipulation and social giving and taking, play helps wire the brain of youngsters, enabling them to develop the skills and awareness necessary to face both the challenges of the world that they have to navigate ‘today’, with the even more risky challenges that are likely to befall them later in life. Foals engaging in their first bouts of social play repeatedly nuzzle their mothers, pull on their manes and tails and regularly nip at their legs and withers. Both their motor skills and cognitive ability become fine-tuned as their mothers, and then their peers, provide regular and important feedback on their playful actions. Play is essentially the social language of youth, as foals and juveniles try to out-buck and out-run each other to see who is most agile and strongest in a play group. In doing so, they learn the social etiquette of dominance, the boundaries of personal space, how to follow and understand leaders and essentially become integrated into groups, thus learning how complex collectives can function as coordinated units. Essentially, through play, they learn the rules of their own society.

Immediately after birth, foals spend over 60 percent of their time with their mothers, but by 3-4 weeks of age they are splitting their time almost equally between mothers and other foals and yearlings. Expanding the pool of contacts is critical for success. Of our North Carolina barrier island horses, those surviving to the age of independence, spent significantly more time chasing, wrestling and even open mouth lip biting—so called ‘play fighting’—with peers than did horses that died before weaning. And studies on the free-ranging ponies of England’s New Forest or France’s Camargue showed that colts engaged in more play fighting than fillies, suggesting that these behaviors are preparatory for the more contentious combative lifestyles that mature males will engage in when competing for mating opportunities with sexually receptive females.

As these examples show, while the play of foals may be boisterous and fun, it is not frivolous. What is striking is that it not only occurs in free-ranging horses where predators are largely absent, but also among zebras, where predation remains high and commonplace. In Kenya, our studies show that zebras are one of the most common prey species of lions; only buffalo are taken more frequently. There, our studies show that play is game-like in the sense that its cognitive form changes as zebras mature. In particular, the social language of play undergoes changes. Just as with people, game playing in zebras gets more complex as zebra foals mature. Relatively simple give-and-take interactions morph into dexterous dances that involve less stereotyped signaling and more nuanced and plastic responses to the actions of others. In many games people play—especially in sporting games—winners display amazing dexterity, abilities to read their opponents’ movements and actions almost before their opponents begin to act, as well as abilities to shape the actions of others on their teams. Having a team member who is able to perform as an exceptional player as well as a leader of others can radically improve the success of a team. In professional sport, such ‘star’ players not only command huge salaries, but as they improve their teams, their fame grows, and additional material and non-material benefits come their way. And often substantial benefits accrue to others on the team. Such adult games involve skills that enhance competitiveness, but also mutualistic interactions that emerge from the coordinated actions of others on the team.

Our studies on zebras show that similar dynamics operate in the games animals play. As zebras mature, play morphs from individual actions into those involving others. As this transformation takes place, the back-and-forth nature of the interactions diversify and change in form and frequency. Most games are shaped by rules and involve some form of signaling. Card games such as Bridge involves bidding; Poker involves negotiating and bluffing; and in sporting games, such as American football, offenses reading defenses lead to play calling that tries to exploit perceived weaknesses. For zebras and other animals, the same communicative back-and-forth and mind-reading applies. So, while the games juvenile equids play may be fun, they are also serious and require the development of an awareness and the cognitive skills to read the actions and infer the intents of others. Thus, early social play, so important for immediate foal survival, can also serve as a precursor for the social games that shape the success of zebras as adults later in life. For humans, monetary rewards and fame are two of the most common measures of success. For animals, it is reproductive success that matters. Maximizing the number of offspring that themselves survive to breed is the best way to spread one’s genes into future generations and gain an evolutionary advantage.

What we see in zebras is that they must manage ‘risk’, which changes in type and degree as they age. To manage risk, youngsters must develop social competence, which begins with social play. By being free of the need to engage in courtship or mating, and by being protected by their mothers and her friends, young zebras live in a simpler world than their parents. When playing with other juveniles in this protected world, and even when trying to entice adults to play, juvenile zebras can test combinations of signals via trial-and-error learning to develop effective communicative phrases. Youthful play within this relatively safe and protected space provides the perfect time to explore and develop new combinations of visual, acoustic and tactile signals that shape successful responses to the actions and movements of playmates.

Take the ‘snapping’ signal, for example. Snapping is when zebras clap their mouths and teeth open and shut rather than thrusting their mouth forward in an attempted bite, and is used differently as zebras age. Foals snap when approaching other zebras as a form of submission, indicating that they come in peace; juveniles snap when greeting others as co-equals, indicating that they come to develop and affirm affiliations; and adults snap in affiliation, when initiating aggression as well as when submitting after losing contests, suggesting that play continues into adulthood, facilitating tolerance and cooperation when coordinated collectives may be needed for all in the group to succeed.

A zebra’s world is full of stresses. Predators are abundant and the availability of food and water cycles through booms and busts. Long periods of drought make it extremely difficult for both adults and youngsters to scrape the bare ground for enough forage to maintain strong and healthy bodies. Moreover, drying of watering points forces groups to predictably visit rare and remaining watering points where predators lurk, and larvae of gut parasites are abundant. While it may seem sensible under such conditions for every zebra in a group to focus on foraging and drinking, our findings reveal that social niceties—especially social play—are not abandoned. Indeed, nursing mothers have elevated needs for food and water. But their foals continue to badger them to play. If these mothers were to accede to their foals’ demands, they would be distracted and unable to consume enough resources to supply their young with enough milk. What’s a mom to do? What emerges within groups, is that stallions and non-lactating females intercede to solve the tradeoff. Stallions increase their vigilance and keep all other adults away from lactating females. And non-lactating females ‘adopt’ the foals during such challenging times, letting them run about, playing with them when they want to play and supervising their play with juveniles. In this way, all three forms of play continue to develop on schedule. By drawing on the social roles of group members, zebras enable foals to benefit from play without forcing the mother to reduce its foal’s nutritional needs.

While the ‘horseplay’ of equids can appear wild, mischievous and good fun, it is neither frivolous nor a luxury of youth or good times. Initially, play is solitary as foals race about and toy with novel objects. Such play never ceases, though, since throughout life, practice makes perfect and staying in good form is essential. Fleeing from predators and navigating social challenges require being healthy, agile and aware. Learning social etiquette without incurring harm requires mastering the give-and-take associated with understanding social dominance, personal space and balancing competitive and mutualistic situations, all of which develop through playful interactions when young, to be applied throughout life. Muted social play when growing up provides the opportunity to explore the many subtle rules that will enable the smooth functioning of the ‘team’ an equid joins in later life. In this way, every animal is poised to win by living another day and attempting to spread as many genes as possible into the next generation.

The most interesting idea here is how zebras manage the tradeoff between maternal nutrition and foal development through collective care. The "snapping" signal evolving from submission to affiliation to aggression across life stages is fascinating, basically the same gesture acquiring contextual meaning through experince. This challenges the notion that animal communication is purely hardwired instinct.