Playing Chicken

Leslie Scott tells the story of how the shy but fearless jungle fowl became both the object and subject of play.

Before we get into the subject of playing chicken, or even playing with chickens, literally or metaphorically, I’d like first to talk about the Gallus Gallus Domesticus itself; and about the relationship between humans and chickens which is, well, complex to say the least, dating back at least 10,000 years.

Given that chicken is the ubiquitous food of our times, (worldwide over 50 billion are slaughtered for human consumption each year), it is perhaps surprising to hear that many experts believe that the red jungle fowl, gallus gallus – a shy forest bird that lacks the ability for long – distance flying - was originally domesticated not for its flesh, but for symbolic and ritual purposes; and for sport, such as cock-fighting in which two male chickens were (still are, albeit illegally in most countries) encouraged to fight each other to the death while spectators gamble on which of the two cocks will survive.

Over a period of a few thousand years, these domesticated fighting chickens were carried – kicking and squawking – from southern to western Asia, that is, Mesopotamia, and then on into Egypt. Apparently, the first appearance of the likeness of a cockerel on an Egyptian monument dates from the time of the New Empire (1580 - 1090 BCE). However, it would be another thousand years or so before the bird, or more accurately, its eggs, formed any significant part of an Egyptian’s diet, as it took this long to master the technique of artificial incubation. This was no mere child’s play. Most chicken eggs will hatch in three weeks, but only if the temperature is kept constant at around 99 to 105 degrees and the relative humidity stays close to 55 percent, increasing in the last few days of incubation. The eggs must also be turned several times a day, lest physical deformities result.

The Egyptians constructed vast incubation complexes made up of hundreds of ‘ovens’. Each oven was a large chamber, which was connected to a series of corridors and vents that allowed ‘egg attendants’ to regulate the heat from fires fuelled by straw and camel dung.

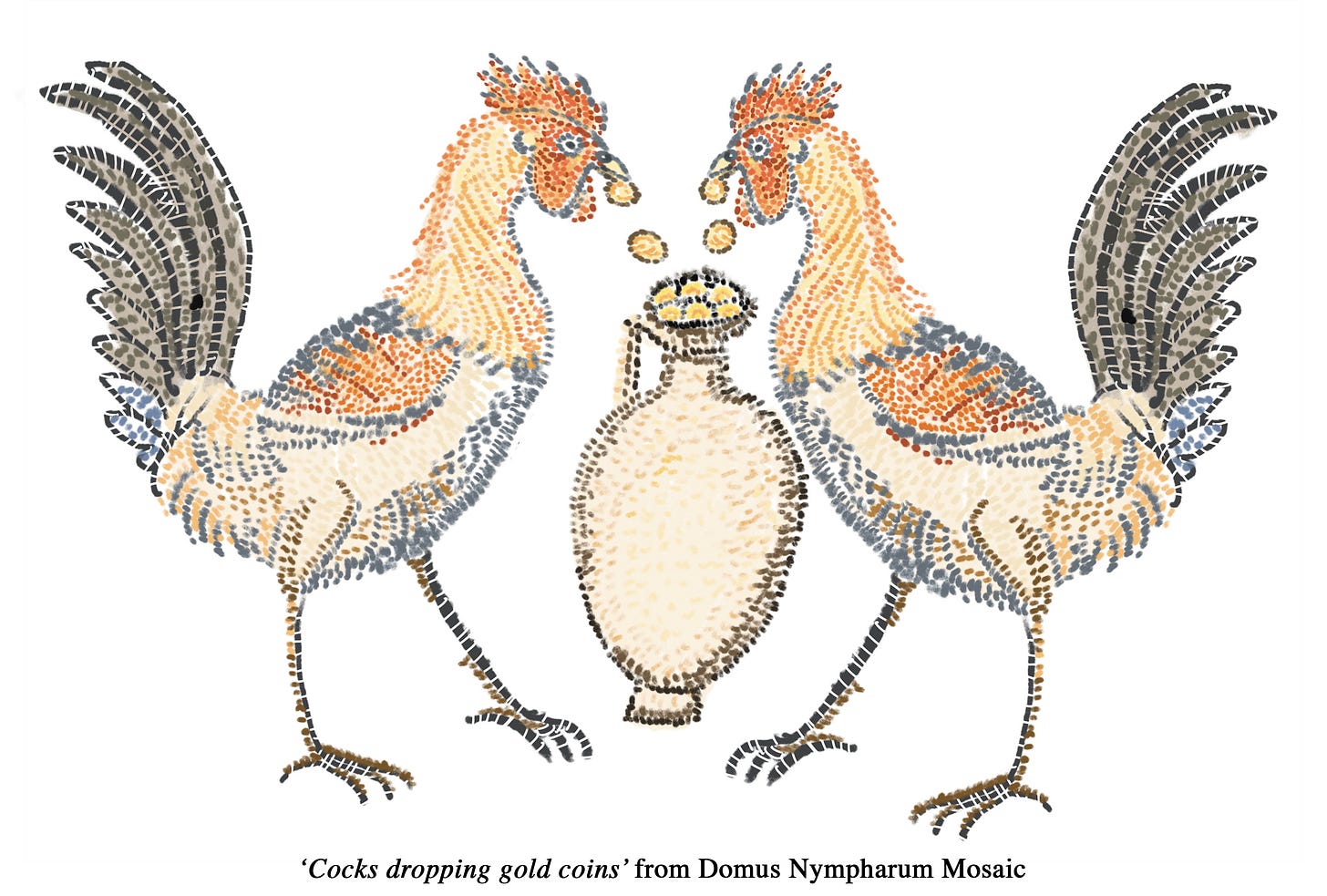

While artistic depictions of rooster combatants are scattered throughout the ancient Greek world, there is little evidence of the Greeks of that era eating much if any chicken. But, judging from the quantity of chicken remains that have been found in archaeological assemblages around the Mediterranean, by the time Greece had fallen to the Romans circa 146 BCE, the wealthy were certainly raising chickens not only for sport but for the pot, too. In fact, chickens became a great delicacy throughout the Roman Empire, whose citizens had learned to stuff birds before cooking, and break eggs to make omelettes – though not yet in England, apparently, where, as late as 55BCE, Julius Caesar was surprised to note that the Britons ‘only rear their fowls for amusement.’ Britons might have come late to the table, but in their own good time they did acquire a taste, first for chicken, then for chicken eggs (or vice versa?) – big-time. In the UK today, over nine hundred million chickens are currently consumed every year and over thirty-six million eggs eaten each and every day. Yet it is wasn’t until Queen Victoria banned cock-fighting and cock-throwing that the British stopped raising fowls for amusement, too.

As late as 1674, Charles Cotton, the author of The Compleat Gamester, was still promoting cock-fighting as a most ‘gentile game’….’a noble recreation’ …. a ‘pleasing art’…. a sport or pastime so full of delight and pleasure that ‘I know not any game that respect is to be preferred before it’.

Cock-throwing, or cock shying, remained an immensely popular, crowd-pleasing blood sport right up until the late 1800s, despite its many critics, which included Hogarth, who in 1751 railed against such brutal play, claiming it to be the first stage in a ‘slippery slope’ in his ‘Four Stages of Cruelty’.

Traditionally associated with Shrove Tuesday (the day when Christians go to confession to be shriven of their sins in preparation for Lent), the game involved restraining a cock and pelting it with sticks and stones until it died of its wounds. If the bird had its legs broken or was lamed during the event, it was sometimes supported with sticks in order to prolong this merry game. The person who threw the killer shot won the game and claimed the rooster’s battered corpse – to eat, one presumes.

This bloody game’s origins are a little hazy, though it seems to have been peculiar to England, where it was popular at least as far back as the fifteenth century. Sir Thomas More (who is venerated in the Catholic church as a saint) was known to brag of his skill as a boy at ‘casting a cockstele’.

It is possible that ‘cock throwing arose during an anti-Gallican phase of British Culture, from traditional enmity towards the French, for which the cock played an emblematic role’ (The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1737). After all, there have been ‘anti-gallican phases of British Culture’ since 1066, and the Gallic Rooster was and still is the official national emblem of France.

Meanwhile, as the medieval English boy honed his skills at lobbying deadly missiles at a trussed male chicken, across the channel, the French man played le jeu de poule, a gambling game which was marginally less beastly than cock-throwing. In this game, the target cockerel was allowed to run about unrestrained while players, who had first placed bets in a pot, took turns to hurl a stone at the poor bird. The first person to hit the chicken won the game and all the money in the pot. It’s not clear what happened to the poor run-ragged rooster, but as like as not, this tough old bird was tenderised by stewing it as a tasty little coq-au-vin.

Apparently, due to this game, any ‘pot’ of money wagered in gambling games came to be known as poule in France, which morphed into pool in English; and, on the basis that gamblers ‘pooled’ their money, people started to pool other resources, which is why we ended up with the carpool, the typing pool and, more recently, the gene pool. If you think about it, this must mean that we humans are made up of little bits of gallic rooster, etymologically speaking. Given the above, one might wonder when and why did these illustrious, ferocious creatures, which ‘ fight not for the gods of their country, nor for the monuments of their ancestors, nor for glory, nor for freedom, nor for their children, but for the sake of victory, and that one may not yield to the other’ (Themistocles), come to be seen as such chicken-livered, chicken-hearted cowards, metaphorically speaking?

Playing Chicken, as in running scared

One of the earliest examples of ‘chicken’ as synonymous with ‘coward’ is found in the Pacata Hibernia: History of the Wars in Ireland During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, which was first published in London in 1633. And I quote: ‘..but the rebels not finding the defendants to be chickens, to be afraid at the sight of every cloud or kite…’.

Given that the chicken is a prey animal whose natural habitat is the forest floor, I would suggest that it is totally legitimate for it to be wary of open ground and ‘be afraid’ at the sight of a predator circling above. Under the circumstances, the chicken’s dash for cover seems a wise strategy, yet we choose to consider this behaviour craven. Even Bob Dylan has subscribed to the idea of the chicken as gutless.

Saying, “Death to all those who would whimper and cry”

And throws down a barbell and points to the sky

Saying, “The sun isn’t yellow, it’s chicken"

- TOMBSTONE BLUESAs an aside, while we’re on the subject of the colour of cowardice, you might be interested to know that it is a gene from another ferocious wild bird of colour, the grey junglefowl (Gallus Sonerretii), that is responsible for the yellow pigment in the legs and different body parts of most domesticated chicken breeds.

Anyway, it is both the chicken as coward and the fearless, unyielding fighting cock that are being evoked when Playing Chicken, a game that came to fame, in fact achieved notoriety, in 1950s America.

One version of the game, as portrayed in the film Rebel Without a Cause (1955), became a defining scene in 1950s American cinema.

The scene takes place at night on a cliffside near the ocean, where a group of disaffected youths has gathered to watch a dangerous contest between Jim Stark (James Dean) and Buzz Gunderson (Corey Allen). The two boys have agreed to a ‘chickie run’ to prove their courage and settle their rivalry.

Jim and Buzz are to race two stolen cars straight towards the edge of a cliff. The first to jump out of his car will be considered the ‘chicken’, and the last to stay in wins.

The cars line up side by side. The onlookers stand back, cheering and shouting. The engines roar as Jim and Buzz look straight ahead, their faces lit by the dashboard lights. After a signal, both slam on the gas, hurtling toward the cliff edge. Wind whips through the open car windows; the music and ambient sounds heighten the suspense. Jim leaps from his car at the last possible second, rolling to safety. Buzz tries to jump too - but the sleeve of his leather jacket catches on the door handle. He can’t escape in time, and his car plunges off the cliff, exploding on the rocks below.

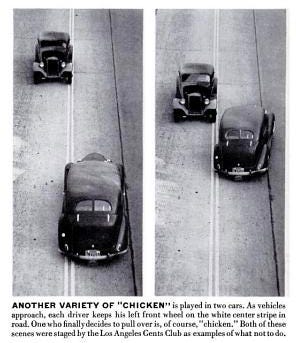

The original version of the game of chicken, as played in towns around America, involved two teenagers driving their own cars at high speed towards one another, with the first to swerve out of the way being dubbed a ‘chicken’. While certainly dangerous, this was a considerably less lethal game than the on-screen ‘chickie run’. So it is chillingly ironic, if true, that according to one account, James Dean, was playing this version of chicken when he was killed in a car crash a few months before Rebel without a Cause was released. As this story goes, the other driver didn’t swerve, not because he was so very brave, but because the sun was in his eyes. He hadn’t even seen Dean’s car coming towards him. It would appear that Dean’s ‘opponent’ had no idea he was playing a game.

Very few people of any age owned cars in 50s Britain, so it seems unlikely that even the most disaffected young Brits would have been found playing chicken at that time. However, the game was certainly well known enough for Bertrand Russell, the British philosopher, to famously compare playing chicken to nuclear brinkmanship. ‘As played by irresponsible boys, this game is considered decadent and immoral, though only the lives of the players are risked’. But played as ‘nuclear chicken’ by government officials, the game would be become absurd and extremely dangerous. The players would be risking not only their own lives but also those of many hundreds of millions of human beings. Russell warned that ‘…the moment will come when neither side can face the derisive cry of Chicken! from the other side’. At which time, ‘…the statesmen of both sides will plunge the world into destruction’.

In his 1964 film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Stanley Kubrick presents a dark satire of Cold War brinkmanship, using the metaphor of a political game of chicken pushed to its most disastrous conclusion. The United States and the Soviet Union engage in a high-stakes strategy of mutual deterrence, each relying on the threat of total nuclear retaliation to keep the other in check. This delicate balance collapses when a rogue U.S. general unilaterally orders a nuclear strike on the USSR, bypassing established chains of command. Unbeknownst to the Americans, the Soviets have recently constructed a ‘Doomsday Machine’ — an automated system designed to launch an unstoppable retaliatory strike if the USSR is attacked. Critically, the Russians failed to inform the U.S. of the system’s existence in time, undermining the deterrence logic of brinkmanship. As Dr. Strangelove (played by Peter Sellers) himself points out, a deterrent is useless if no one knows it exists. The failure to communicate that the Soviets could not ‘swerve’ — that their retaliation was automated and irreversible — turned a dangerous game of chicken into a guaranteed catastrophe. The film underscores how brinkmanship, when combined with miscommunication and rigid systems, doesn’t just risk disaster; it makes it inevitable.

Playing Chicken is still a widely used and widely understood metaphor for brinkmanship; for taking an issue to the limit, to the very edge of a cliff. The ‘game’ depends on an assumption that its players face equally grave risks, and that ‘tipping over the brink’ would be mutually devastating.

Playing Chicken (also known as the Hawk-Dove game), has become a subject of serious research and an influential mathematical model of conflict between two sides. The principle of the game is that while each player prefers not to yield to their opponent, the outcome where neither player yields is the worst possible one for both players. Mind you, this theoretical formulation of the game doesn’t appear to allow for chance coming into play, whereas in reality, there is almost always an element of chance, or incalculable risk involved when playing chicken. Events beyond the control of either side can trigger a catastrophic outcome.

Playing with a Chicken

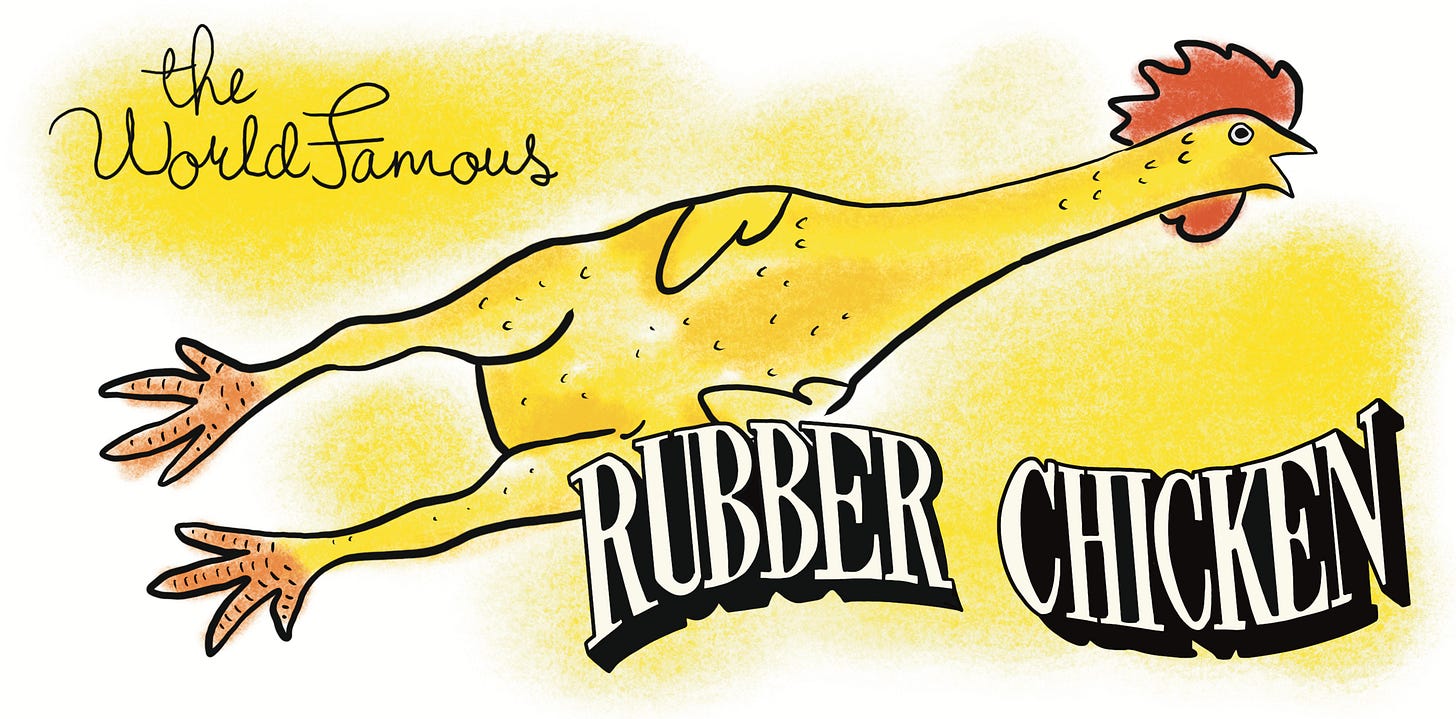

For now, let’s park playing these seriously dangerous games of Chicken and move on to something a little more playful, which is playing with a chicken – a yellow rubber one, to be precise.

Throughout history, the cock has been considered a mighty creature. In Greek mythology, it was sacred to Apollo, god of the sun. The crowing cock put demons to flight, according to the Persians. In ancient Rome, he was considered an oracle, predicting the outcome of war; as reported by Pliny, even the lions were afraid of him. Two fighting cocks on the tombs of Christians represented courage under persecution, and in Norse mythology, the cock was charged with waking fallen heroes and speeding them forth to Valhalla.

Perhaps it’s precisely because it had been held in such high esteem that using a floppy facsimile of a denuded rooster as a weapon seems so ridiculous, and therefore irreverent and therefore funny; certainly funny enough for the novelty company, Loftus International, to have sold many millions of what it claims to be ‘The Original’, ‘ WORLD FAMOUS’, ‘realistic’ rubber chicken.

Theirs may indeed be the original rubber chicken as we think of it today, but its origins could be medieval and based on the use of inflated pig bladders attached to a stick and used as props or play-weapons by court jesters or fools. Or older still. The romans played with what they called follis, balls made from inflated pigs’ bladders. And ‘follies’ or ‘fools’ derive from follis, these playful bags of air.

Playing a Chicken

Another aspect of chickens and play that has history – so to speak – is playing a chicken, in other words, dressing up and acting like a chicken, or being depicted as a chicken. Two of several famous examples are:

Charlie Chaplin in Gold Rush, 1925…

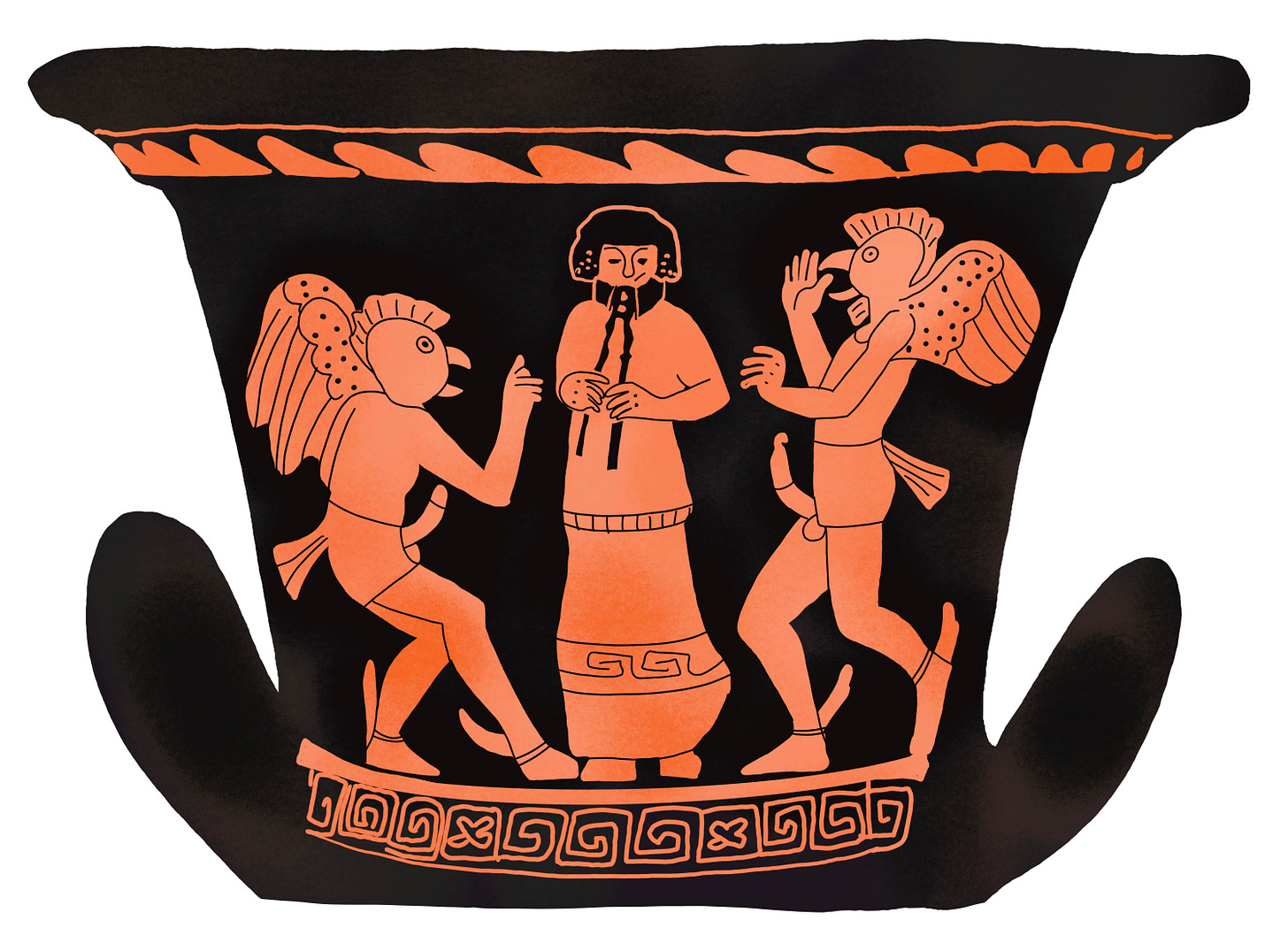

…and this Greek vase depicting The Birds by Aristophanes.

Most, if not all, experts agree that the presence of the piper indicates that it likely depicts a scene from Aristophanes’ satirical comedy, The Birds, which was first produced at the City of Dionysia in 423BC. Two men dressed as fighting cockerels and representing The Old and The New Ideas conduct a furious debate about the growing belief that civilized society was not a gift of the gods but rather had developed gradually from primitive man’s animal-like existence.

Playing Chicken, as in a visual play on words

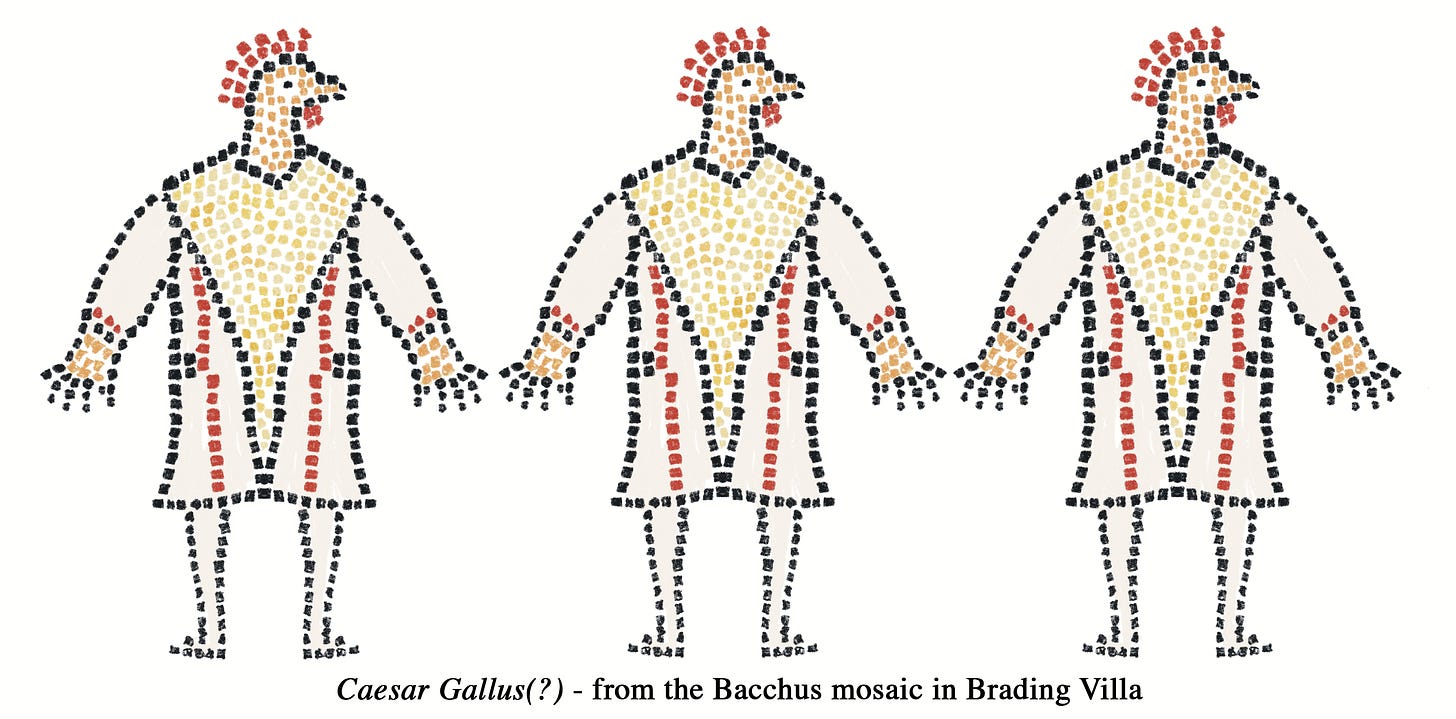

It has been suggested that this very puzzling mosaic in Brading Villa on the Isle of Wight was commissioned by Palladius, a high ranking bureaucrat exiled to Britain in AD361 from his native Antioch, and that the figure of a person with the head and feet of a chicken is a lampoon of the man who banished him; one Caesar Gallus.

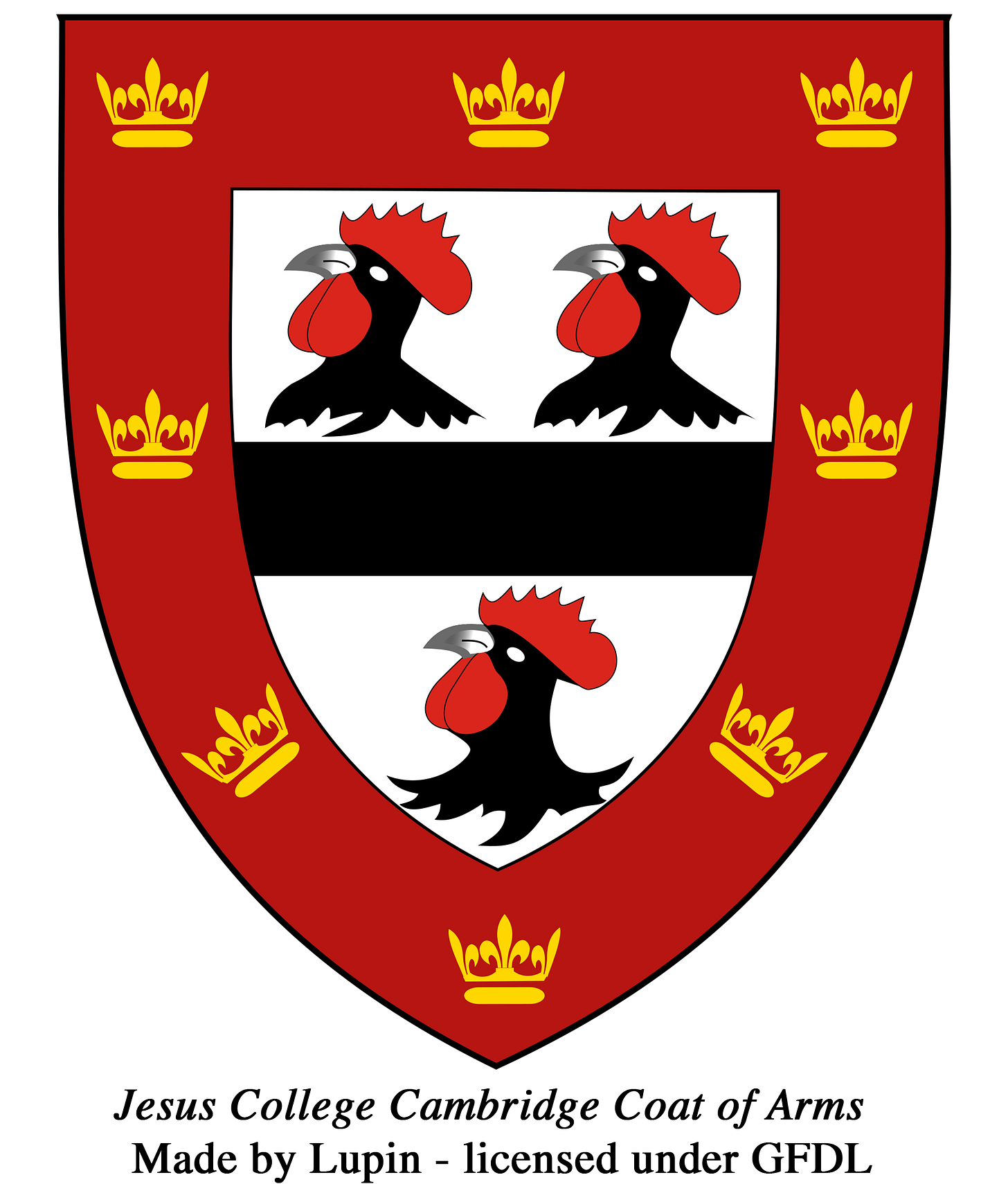

Jesus College Cambridge was founded by Bishop John Alcock in 1496 and the college crest shows the arms of the Alcock family in which the cockerels are heraldic bearings called canting arms – in other words, visual puns – in this case, a play on the word ‘cock’.

Playing Chickens

Finally, there is playing with a pet chicken, and providing toys for pet chickens to play with – which is a thing, apparently – and perhaps no bad thing at that. Given the astonishingly huge negative impact (on the environment) of all the animals we humans breed to eat, maybe it’s time to revert back to raising chickens solely for our own ‘entertainment’, albeit for a somewhat less bloody form of play.

🐓

A compelling, fascinating, intensely readable polymathic excursion into chickenhood! More please!