Playing the Clown

An innocent lark for most until Stephen King took the fun out it for some - writes Bob Peirce

Clowns were not always the playful fellows we think of today – that is, unless you are petrified of them, and we shall come to that shortly. The word ‘clown’ emerged in the mid-1500s to describe rustic, unrefined characters or buffoons, bumpkins or dolts – a range of meanings from patronising to pejorative.

Macaulay, in his great History of England (1849) was probably more patronising than pejorative when he wrote in his account of the Battle of Sedgemoor (1685) that, “the Somersetshire clowns with their scythes … faced the royal horse like old soldiers.” The brave country folk died in their hundreds fighting for the Duke of Monmouth’s ill-fated rebellion against James II (who was unceremoniously relieved of his kingdom only three years later in the so-called Glorious Revolution of l688).

During the 1600s the word ‘clown’ acquired the additional meaning of a fool or jester, and it was used in that sense by Shakespeare and others, but the old definition was also retained. A shift occurred in the early 1800s, and the man responsible was one Joseph Grimaldi.

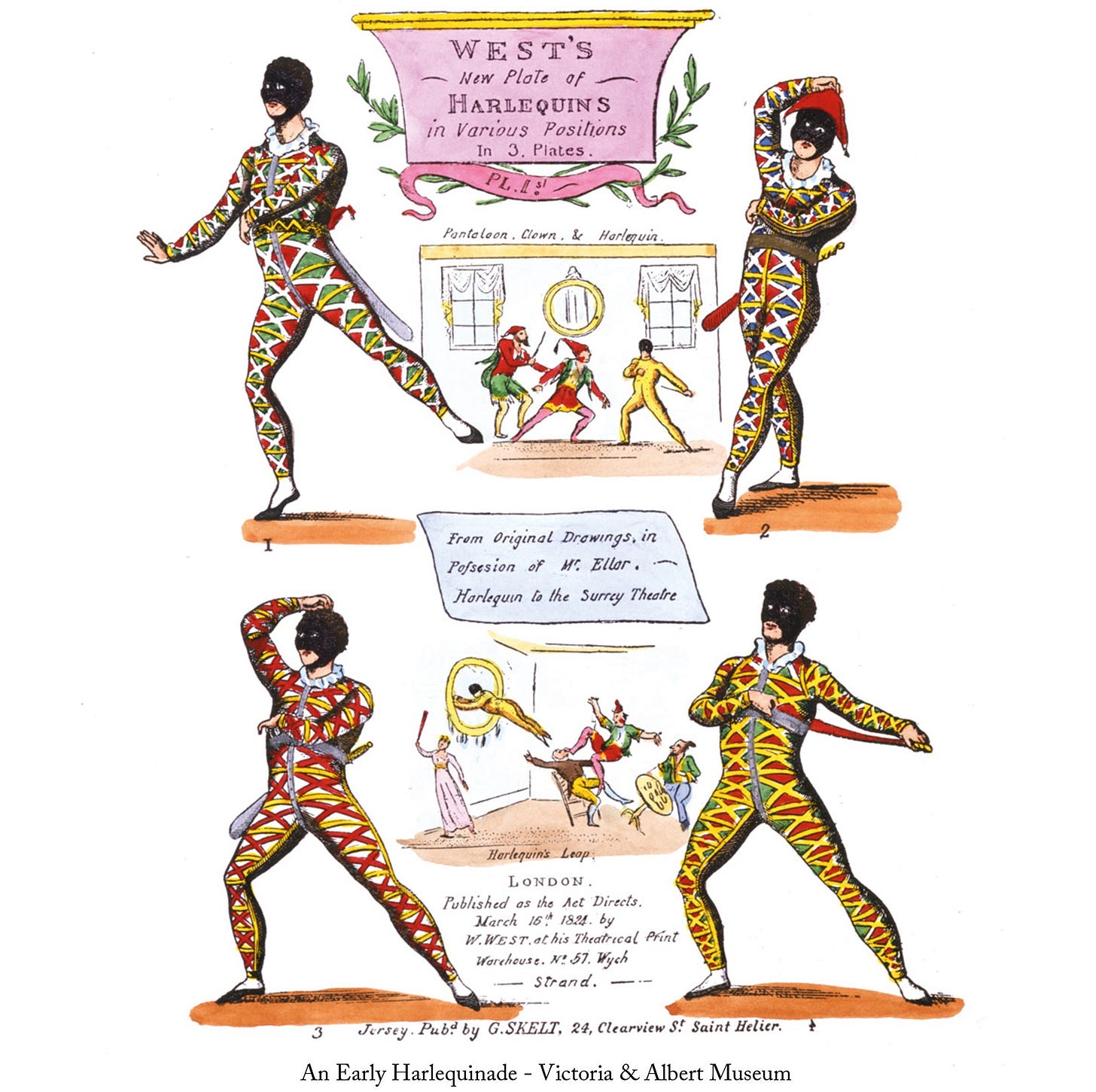

Born into a family of entertainers in London in 1778, Grimaldi began his stage career as a child actor in the Harlequinade - a regular feature of British pantomime, adapted from the Italian commedia dell’arte. The Harlequinade was a comic scene featuring a small cast of familiar characters acting out a familiar plot. The male lead, Harlequin, was enamoured of the lovely Columbine. Her greedy father, Pantaloon, disapproved of their romance because he wanted a better – that is, richer – match for his daughter. He tried to drive them apart with the inept help (or hindrance) of Clown and Pierrot.

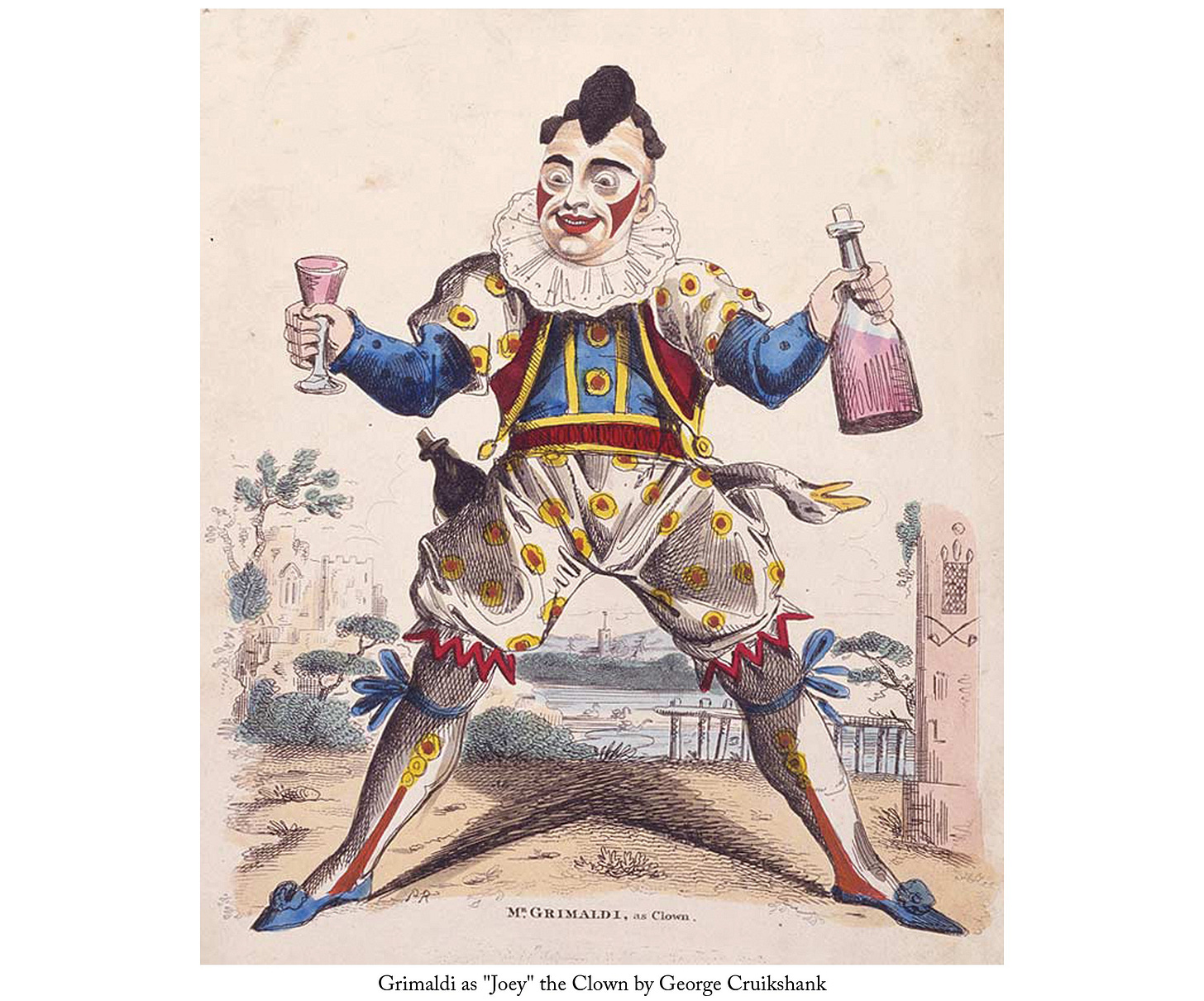

Clown was originally played as a country bumpkin, but in Grimaldi’s hands it evolved into a precursor of the circus clown we recognize today. In the words of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Grimaldi turned the role of Clown from a ‘rustic booby’ into the star of metropolitan pantomime. He adopted whiteface makeup, painted over with exaggerated facial features, and wore garishly-coloured costumes with tassels and ruffs. Eclipsing Harlequin, he became the central figure of the show. Grimaldi was the most popular performer of the Regency period, changing forever the idea of a clown, so much so that clowns were known as ‘joeys’ for generations after he retired, exhausted from the exertions of clowning, in 1823. He died in 1837 and is buried in Joseph Grimaldi Park in the London Borough of Islington.

The next century and a half might be seen as a golden age for clowns, corresponding with the golden age of travelling circuses. Clowns became an indispensable feature of circuses, with outlandish makeup and outfits that owed everything to Grimaldi’s trailblazing example. Playing the clown became an art form, and the best practitioners could become famous.

Coco the Clown was one of the best known in Britain in the middle of the twentieth century. Nikolai Poliakoff, the son of a cobbler, was born in Latvia, ran away to join the circus at the age of eight and learned his craft from a performer named Vitaly Lazarenko. He was briefly with the Soviet State Circus before going to Britain in 1929, where he joined the Bertram Mills Circus. In the Second World War, he entertained the troops as a member of ENSA -Entertainments National Service Association. He remained in the United Kingdom for the rest of his life, and was awarded an OBE for his charitable work with children. He is buried in the Northamptonshire village of Woodnewton, the home of Clownfest, a fundraiser inspired by his work.

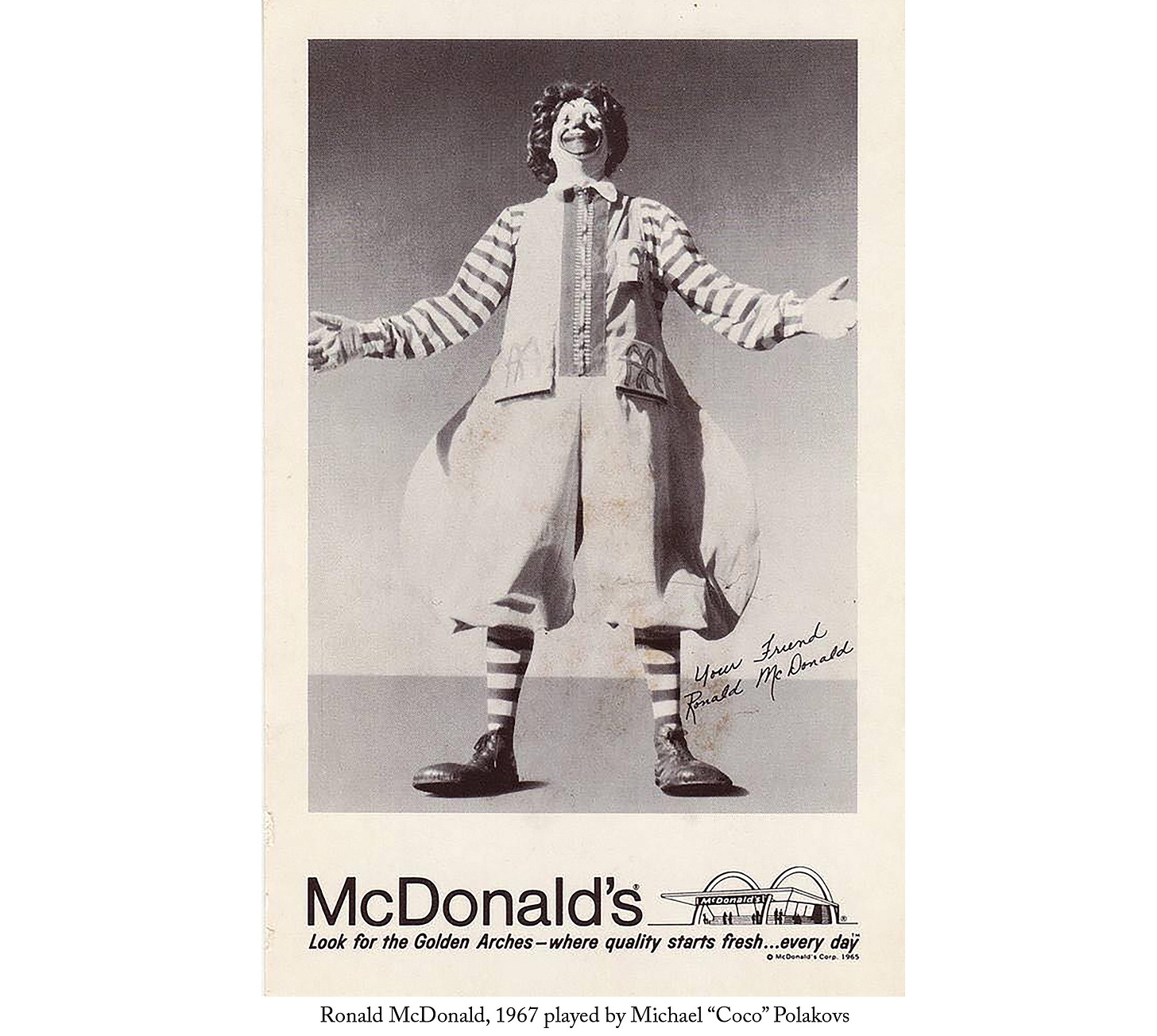

Nikolai’s son Michael took the Coco the Clown character to the United States, performing with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. In 1966, Michael was hired by the McDonald’s fast-food company to refresh their Ronald McDonald clown mascot. Both Michael and his father were inducted into the International Clown Hall of Fame – yes there is one! – in Baraboo, Wisconsin.

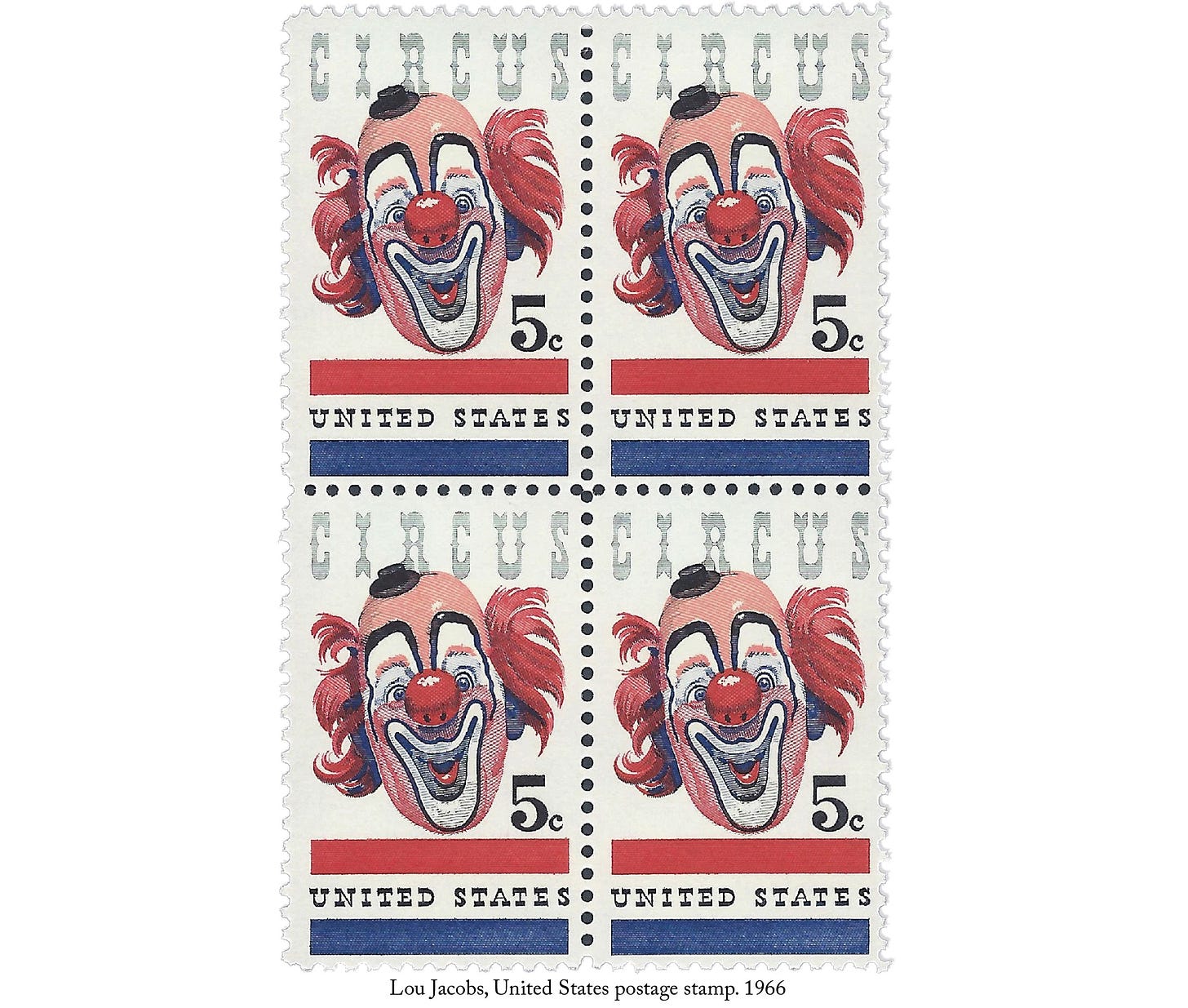

Lou Jacobs (born Johann Ludwig Jacob in Germany), performed with Ringling Brothers for more than sixty years. He is credited with developing the clown car prop, in which a large number of clowns emerge from a small car, and also with the popularisation of the red rubber-ball clown nose. A portrait of Jacobs in his clown make-up appeared on a United States postage stamp in 1966, making him the first living person to be so honoured – not Neil Armstrong as is commonly believed.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, travelling circuses pretty much disappeared, hit both by a shift in public opinion against exploiting lions, elephants and other wild animals for amusement, and also by the rapid growth of entertainment choices in the home. A valiant exception is the extraordinary Cirque Du Soleil, founded in Canada in the 1980s, which uses no animals and plenty of clowns.

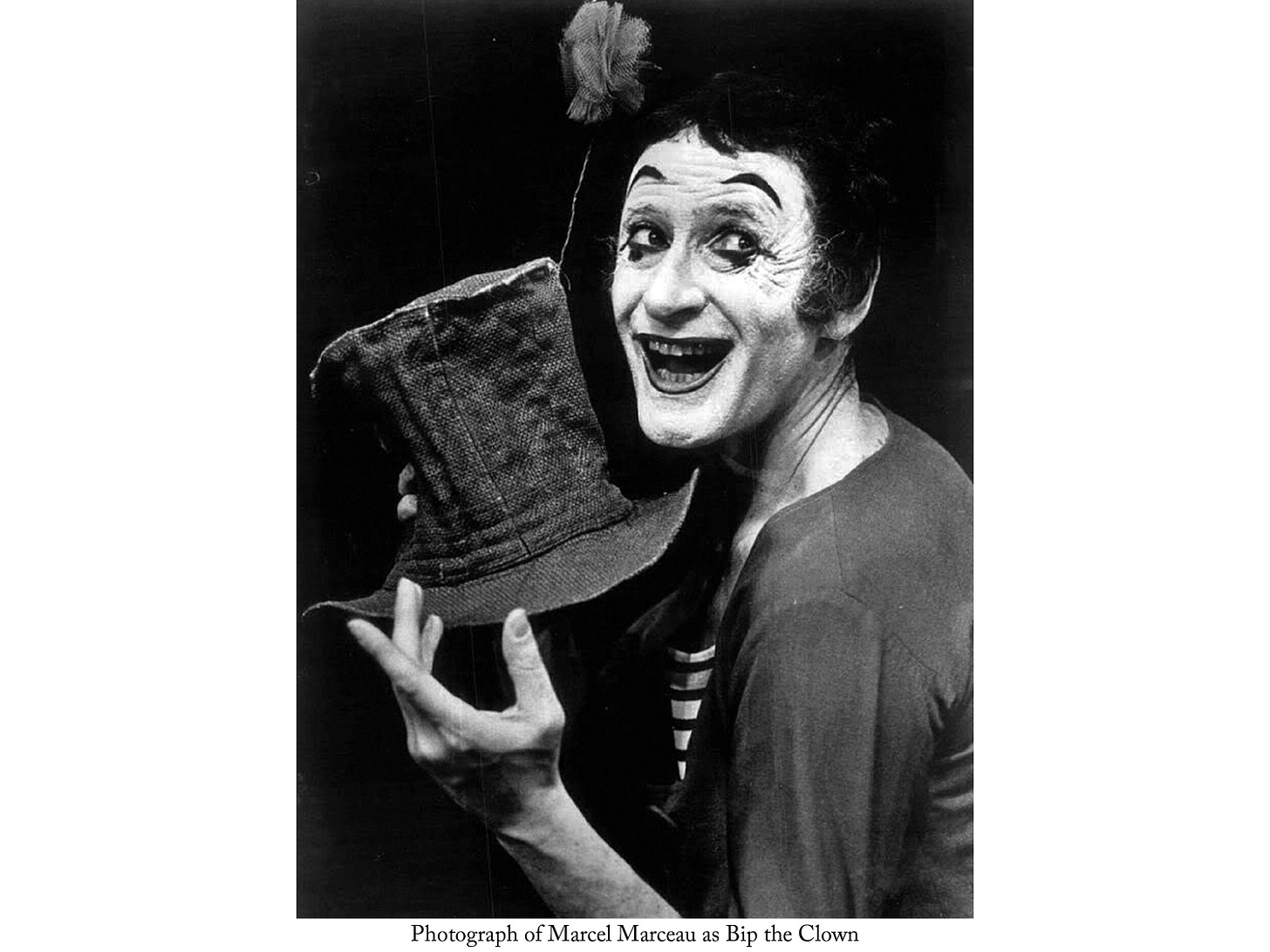

In 1947, the incomparable mime genius Marcel Marceau launched his creation Bip the Clown – white-faced and sailor-suited, radiating emotion and telling stories in complete silence. It was the start of a sixty-year career, worldwide fame, and a golden age for the art of mime. Marceau had been mesmerized by the power of mime since seeing Charlie Chaplin in Gold Rush (1925) as a young child. Their one and only meeting was a chance encounter at Orly airport near Paris in 1967. Marceau later described how he approached “my idol and inspiration” by miming Chaplin as the Little Tramp, and Chaplin responded by miming Marceau miming him. Marceau also kept silent about his teenage years as a Jew in Nazi-occupied France until 2007, when, on his deathbed, he handed his daughters a manuscript about his early life. His father, a kosher butcher, was murdered in Auschwitz. Marcel and his brother joined the resistance and risked their lives smuggling orphaned Jewish children to safety in Switzerland. He used mime techniques to entertain the children and keep them quiet.

‘Playing the clown’ as an idiom can mean joking around in an entertaining fashion but it can also refer to messing around in an irritating fashion. If, for example, a schoolteacher tells you your kid is playing the clown in class, she does not mean that as a compliment.

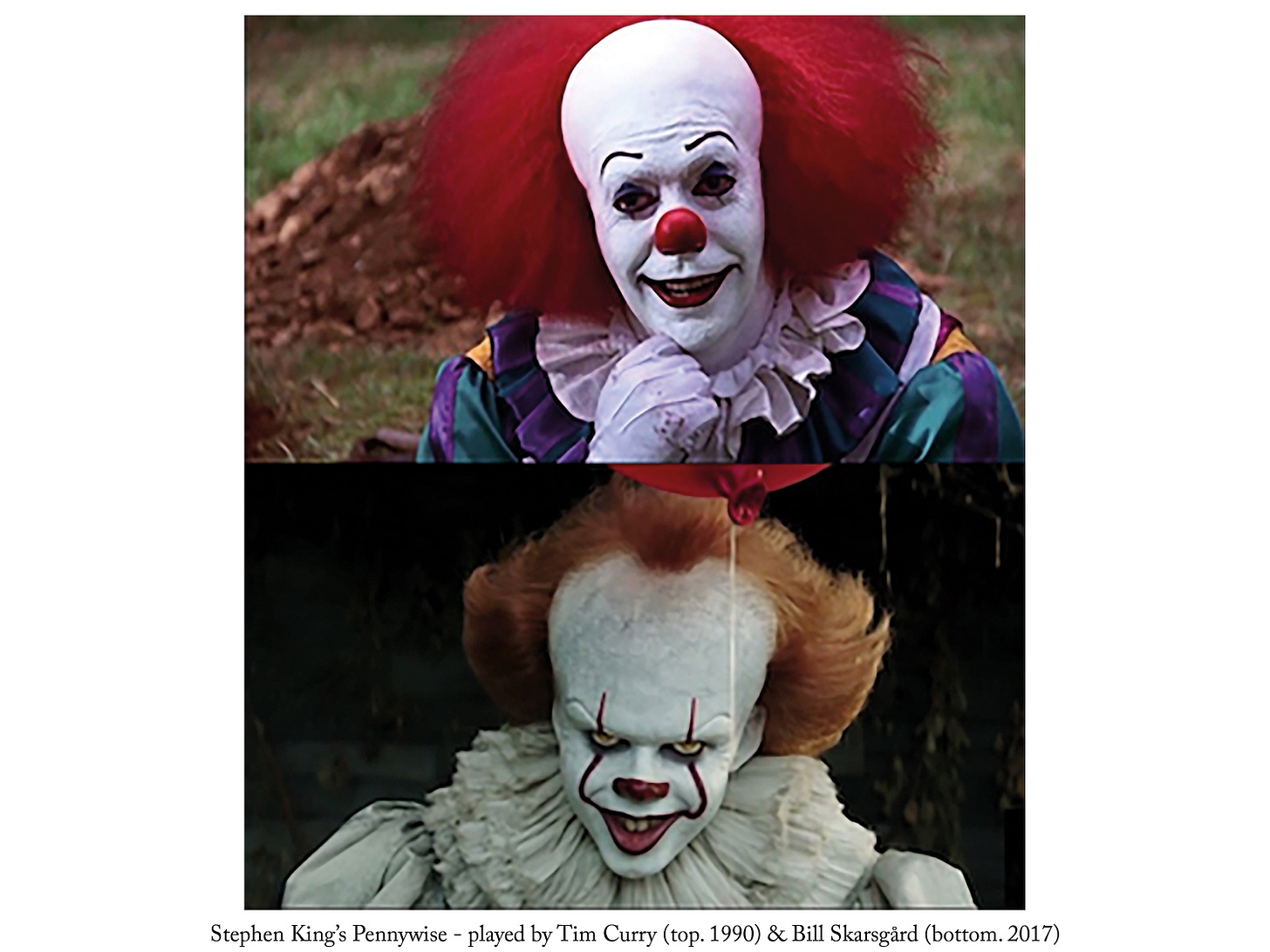

Class clowns, however, are not the darkest cloud hovering over the image of the beloved clown. If Grimaldi ushered in the gilded age of clowning, the blame for tarnishing the gold content should probably be given – at least in part - to the leading author of the horror genre, Stephen King. In 1986, his novel It introduced the world to Pennywise the Dancing Clown, a demonic character that preys on children. A television series based on the book helpfully followed in 1990, with Tim Curry as Pennywise, providing the diabolical visuals needed to change forever the playful image of clowns into something evil. More recently we have had It the movie in 2017 and a sequel in 2019 with Bill Skarsgard playing the role.

To be fair to Stephen King, the ghastly crimes of the Chicago serial murderer John Wayne Gacy, sentenced in 1980 for 33 homicides, did not help the image of the clown; he was known as the Killer Clown because he had dabbled at clowning, but there was no suggestion that he had dressed as a clown when committing his crimes.

Since the arrival of Pennywise, we have also seen the emergence of the word ‘coulrophobia’, the fear of clowns. Such a fear may conceivably have existed before, but if so, it went largely unnoticed. At any rate, no-one bothered to invent a word for it, although people do go to the trouble to invent words for the most bizarre phobias. Someone has coined ‘arachibutyrophobia’ for the fear of peanut butter sticking to the roof of one’s mouth. Back in the day, ‘choking’ might have sufficed for this and other substances blocking the airways.

How common is coulrophobia? To be clear, we are not referring to kids running screaming on Halloween when one of their peers shows up in a Pennywise mask. We are talking about extreme and irrational fear caused by seeing a clown or even a picture of one.

Scientists from the University of South Wales polled almost a thousand people and found that 53.5% were scared of clowns to some degree and 5% ‘extremely afraid’. Extreme fear of heights, by contrast, was reported for only 2.8% and claustrophobia for only 2.2%. Looking at the causes, the researchers found that Stephen King and Pennywise were a significant contributing factor. But makeup also played a part, by masking true facial expression and causing people to worry about what the clown might be thinking or do next. Research continues.

Meanwhile, more films and television shows follow the trail blazed by Pennywise. Old Joe Grimaldi must be turning in his Islington grave. It was all supposed to be such fun, so playful.

🤡