Playing the Fool

Including farting as a career choice and tapping into the softer side of Ivan the Terrible - words by Bob Peirce

Playing the fool suggests that the subject is not really a fool but rather acting the part of one. A parent might scold a child for playing the fool, not because they think the youngster is a dolt but because they believe they are smart enough to know better. In a less pejorative sense, playing the fool can mean simply fooling around in a playful, silly but harmless fashion. This is a common use of the term today.

It might possibly have been the meaning intended by the diarist, Samuel Pepys, when he wrote on February 12th, 1688, that he ‘…staid up a little while, playing the fool with the lass of the house at the door of the chamber...’ However, he had been drinking heartily since noon; he was a twenty-seven-year-old with a powerful libido and his diary is peppered with references to sexual liaisons with barmaids, servants and married women. All things considered, our Samuel probably did not stop at innocent banter with that lass in the tavern, and ‘playing the fool’ meant something closer to our present day ‘fooling around’.

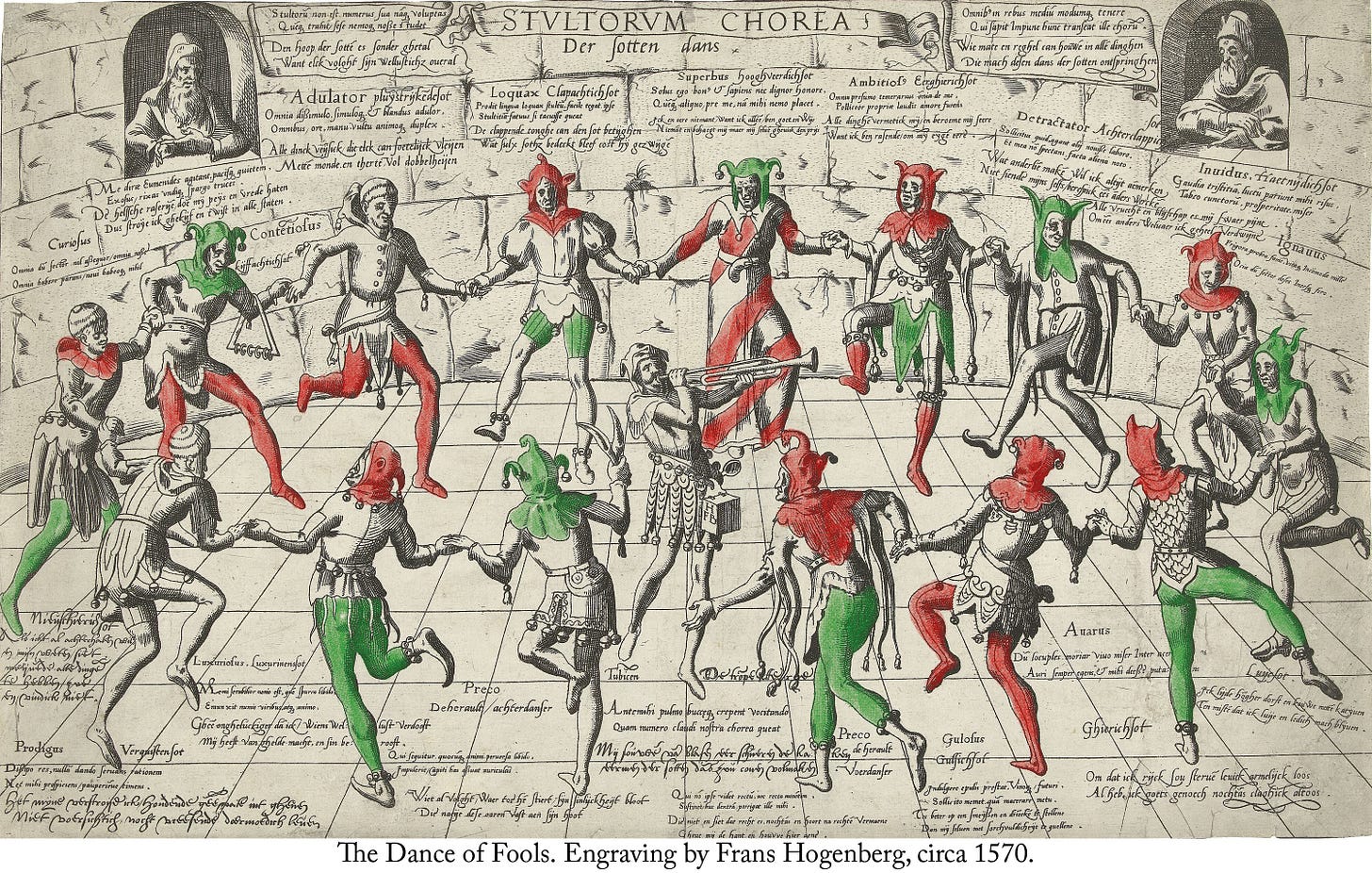

Playing the fool, in the 1600s and before, meant behaving in a manner typical of a jester or a clown. Fools, in the sense of comic entertainers, had been a feature of court life since the Fifth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt (25th century BCE), and would remain so into the 1700s. Some of these ‘fools’ were people with cognitive impairments, kept like pets, along with dwarfs and others with different conditions, for the amusement of kings and aristocrats, and possibly even for luck in some cases. Others were gifted performers, singing, dancing, juggling, storytelling, and ‘playing the fool’ with slapstick humour and clever witticisms. Shakespeare portrays both these types of fool - the ‘natural fool’ and the ‘wise fool’ – in his plays.

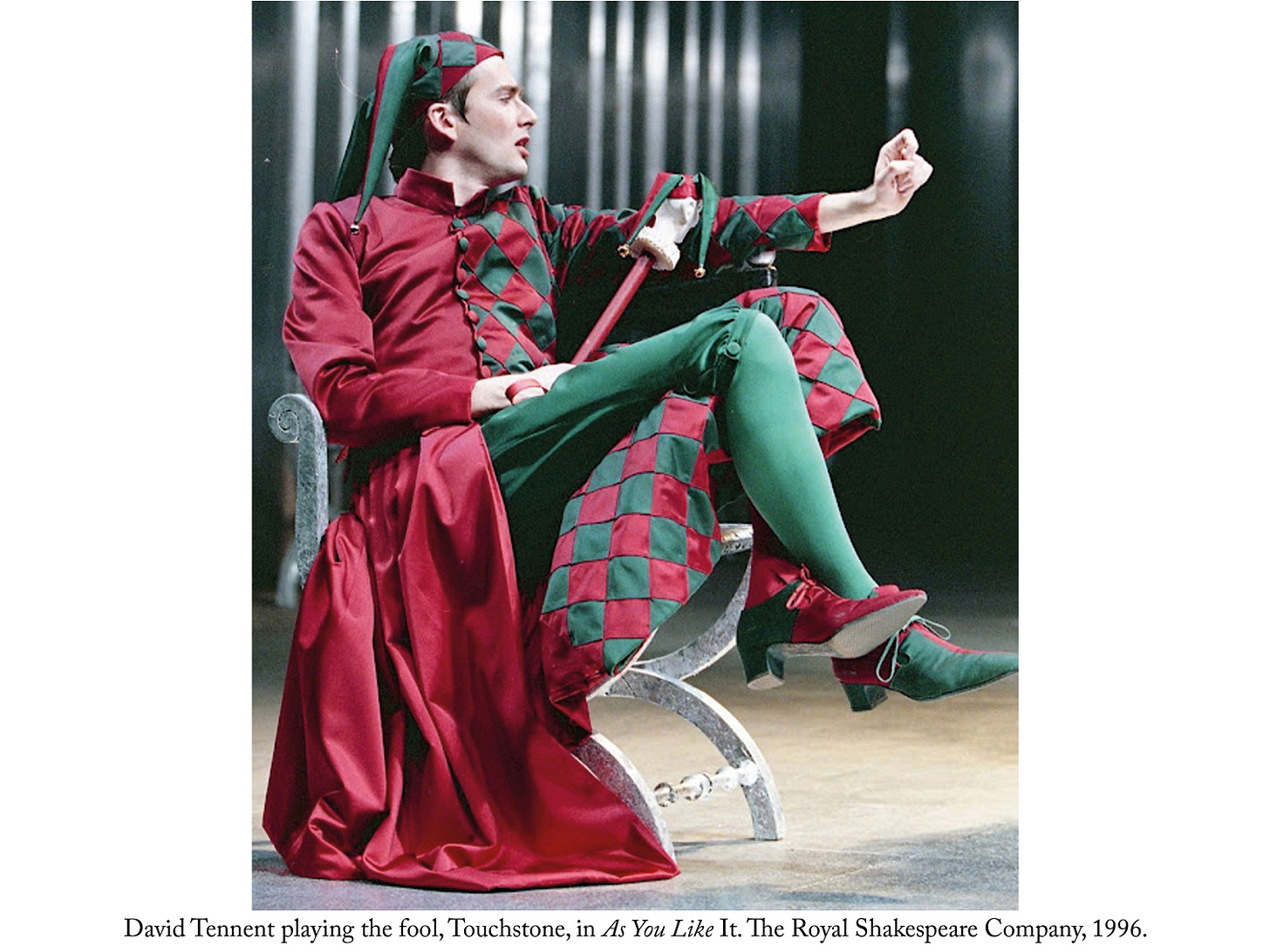

It is, of course, the wise fool who can be said to ‘play the fool’. And it took skill to do so. As Viola says in Twelfth Night about Feste, “This fellow’s wise enough to play the fool … and to do that craves a kind of wit.” Feste himself says “Better a witty fool than a foolish wit.” Feste, and Touchstone in As You Like It, are used by Shakespeare not only for comedic effect but also to provide insight - to say wise things in an amusing way. Wise fools can be symbolic of common sense and honesty.

In the real world, monarchs - some of them at any rate - also gave their wise fools licence to speak truth to power. They could sit at the master’s table and say whatever came into their heads. No doubt Kings preferred the barbs to be directed at their courtiers rather than themselves. Martin Luther described himself as a jester, perhaps in a bid to claim a kind of jester’s immunity as he spoke out about the failings of the Pope and the Catholic Church. The Vatican, incidentally, also had a court jester, until the position was scrapped by Pope Pius V as part of his Counter Reformation spring cleaning.

Jester’s immunity was not absolute, however, in fiction or in fact. The fool in King Lear is whipped for going too far. Francois I of France sentenced his fool, the famous Triboulet, to death for overstepping the bounds and making fun of the queen. Very generously, the king offered Triboulet a choice of how he wished to die, thinking no doubt that he would select beheading by the sword, which was considered preferable to the axe, and certainly to hanging and disembowelment. Triboulet cleverly chose ‘death by old age’, and Francois - clearly a softie at heart – gave him a reprieve.

Court jesters could do quite well for themselves. The Domesday Book, a meticulous ledger of property in Norman England in 1086, records that Adelina, a joculatrix (female jester), held land at Upper Clatford, Hampshire, directly from King William (the Conqueror).

A century later the notorious Roland le Pettour (aka Roland the Farter) was granted a manor in Hemingstone, Suffolk. On Roland’s retirement from court jesting, King Henry II demanded of him that he return once a year at Christmas to perform his signature trick – unum saltum et siffletum et unum bumbulum - one jump, one whistle, and one fart (all at the same time). This festive tradition appears to have ended with him; at any rate it is not a feature of the Royal Family’s modern Yuletide gatherings at Sandringham.

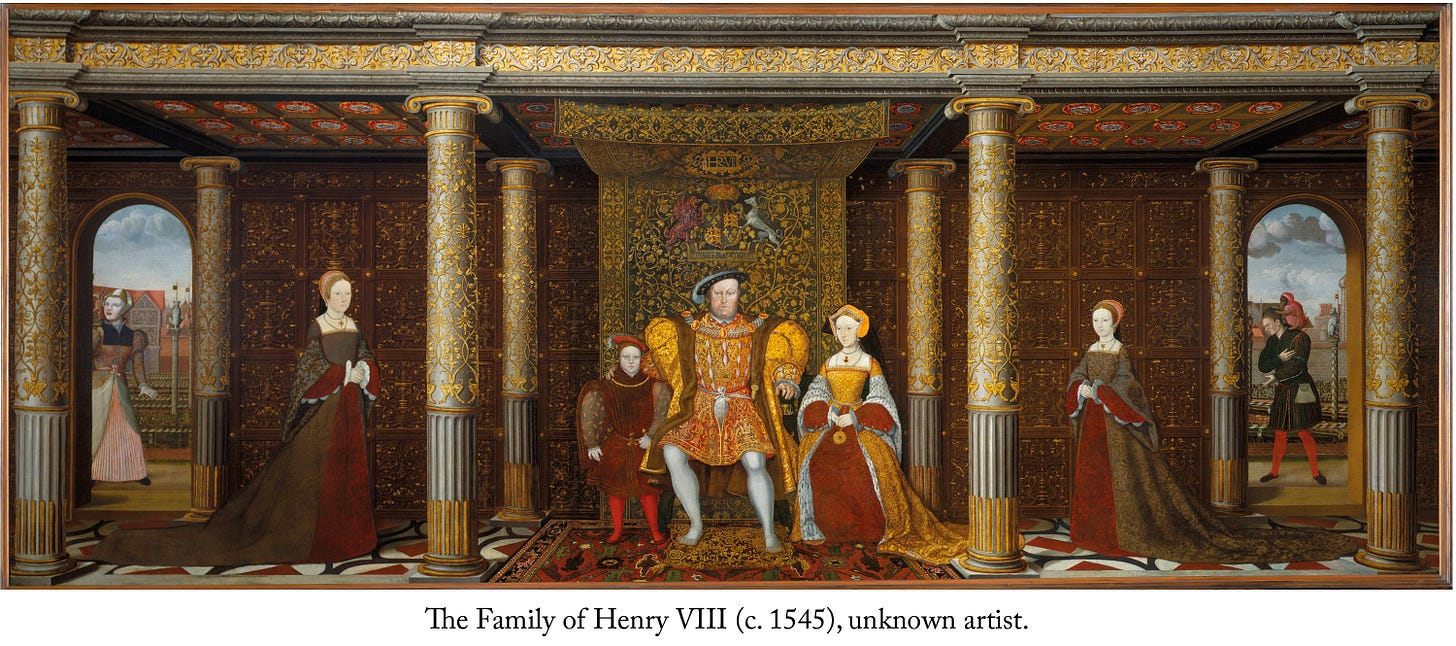

Henry VIII had a favourite fool, Will Somers, described as very short and stooped in stature and hollow-eyed. He may have been married to one Jane Foole, whose job it was to amuse the queen. Will and Jane are believed to be the figures shown in a portrait of Henry and Anne Boleyn, which hangs in Hampton Court Palace. Historians are unclear whether they were playing at being fools, or whether they were just, well, fools.

Will had a close shave with Henry when he once referred to Anne Boleyn as a ‘ribald’ and Princess Elizabeth as a bastard, causing the enraged King to threaten to kill him with his bare hands. He had to take refuge at the home of Sir Nicholas Carew, who had dared him to utter the offending words (which lends credence to the view that Will was a ‘natural fool’). Henry eventually calmed down, and Will was able to return to court, becoming a close companion to the King. He is pictured with Henry in the King’s personal prayer book, dating from the 1540s, and had “admission to the King” at all times, “especially when sick or melancholy”, according to a contemporary account. Henry spent the last decade of his reign in pain from an unhealed jousting injury to his leg, adding to the poor man’s woes from his marital and other issues. Will’s company provided light relief.

Will Somers outlived Henry and continued to serve at court through the reigns of Edward VI and Mary, retiring shortly after Elizabeth became Queen. He may have been a ‘natural fool’, but he appears to have known how to play the part well over the long term. His reputation endured years after his death in 1560, notably in the writings of the actor Robert Armin, who did much to develop the role of fools in the plays of Shakespeare.

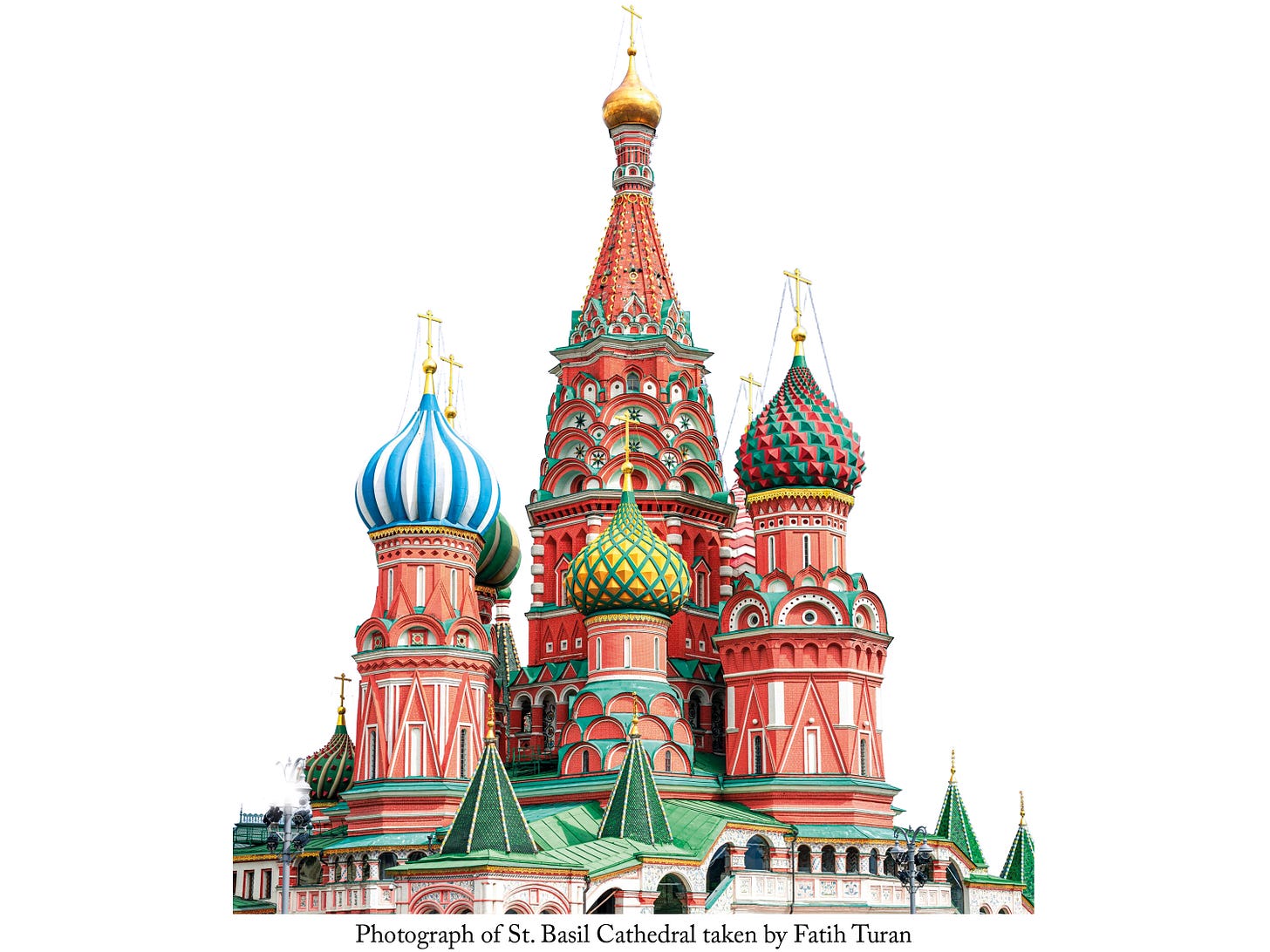

Even Ivan the Terrible of Russia, whose bad moods made those of Henry VIII seem like mild irritation, could take time out of his busy schedule of purging and castrating ministers and massacring entire cities to appreciate a good fool. Basil, known as the Fool for Christ, was a ‘holy fool’. A former apprentice cobbler, he took to walking around Moscow barefoot and naked, even in winter, behaving in bizarre ways that came to be interpreted as messages from God. A common story is that he marched through a market tipping over stands of pastries and jugs of kvass. After he was beaten by the angry vendors, thanking God as the blows rained down on him, it was discovered that the merchants were selling wares unfit for consumption. Basil was seen as an agent of God exposing wrongdoing. He also acquired a reputation for clairvoyance, healing the sick, curing the blind, walking on water and, most remarkably of all, for being the only man who could scold Ivan and get away with it.

Not only did he get away with it, but when Basil died in 1557, Ivan renamed a cathedral in his honour. The ‘Fool for Christ’ has been venerated ever since as an important saint of the Orthodox Church, and St. Basil’s is the most striking building in Moscow.

A British Ambassador to Russia in the 1580s, Giles Fletcher, observed holy fools “stark naked save a clout about their middle, with their hair hanging long and wildly about their shoulders and many of them with an iron collar or chain. These they take as prophets, and men of great holiness, giving them a liberty to speak what they list without any controlment …”

Erasmus, in Praise of Folly, posited that fools were closer to God than other people, because they were untainted by sin and had an innocence of thought. This was widely believed in sixteenth century Europe.

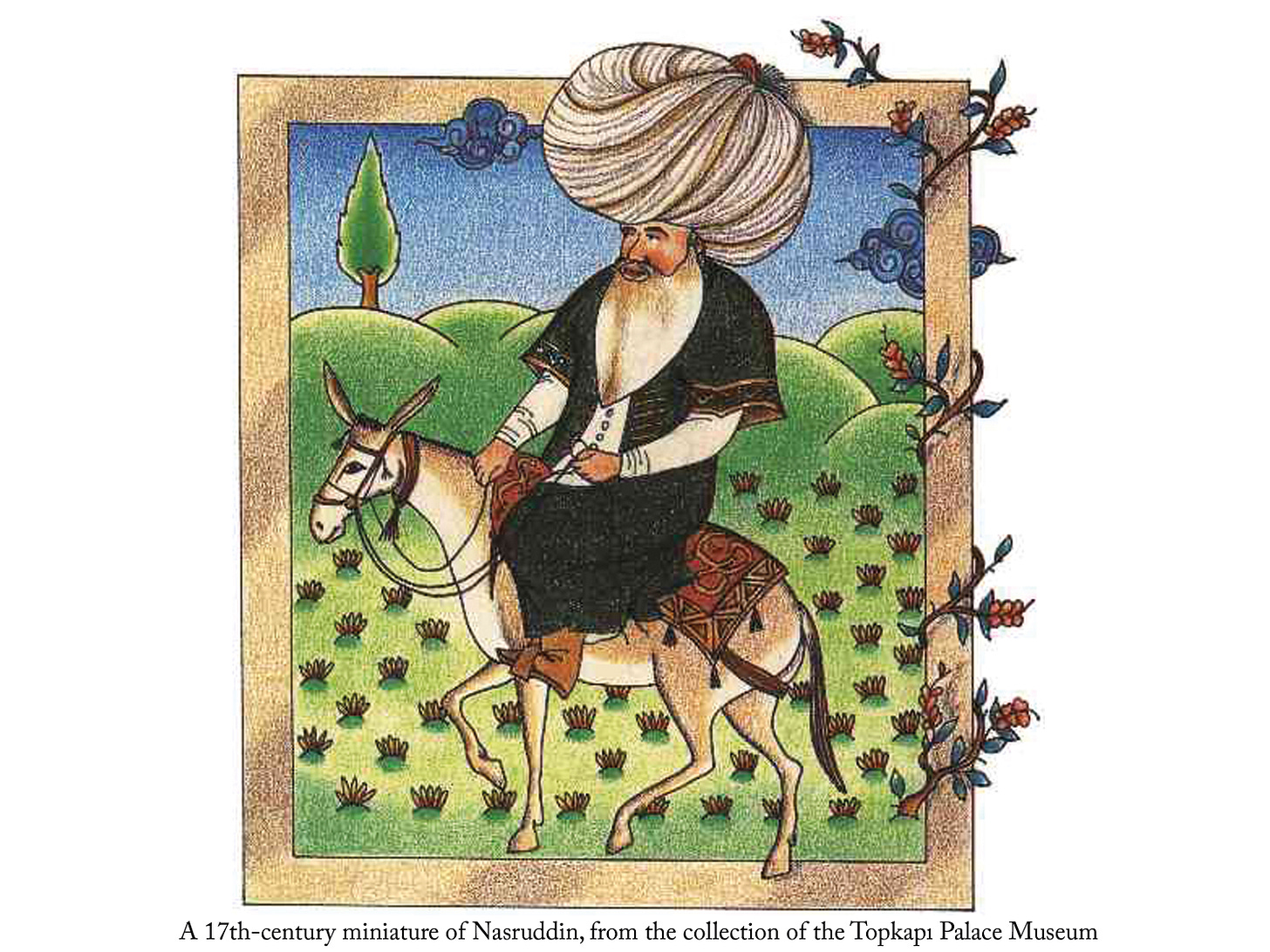

The Islamic world also has had its version of the holy fool, the famous example being Mulla Nasruddin. His origins are unclear; he may have lived in the thirteenth century in what is now Turkey, where an annual festival celebrates him to this day. Thousands of stories are told about him throughout the Islamic world, usually presenting him as an amusing holy fool and conveying a pedagogic message. Some of the stories resemble Aesop’s Fables. The British-based Sufi teacher Idries Shah published several collections in English, as part of his lifelong work to introduce Sufist thought and wisdom to a Western audience.

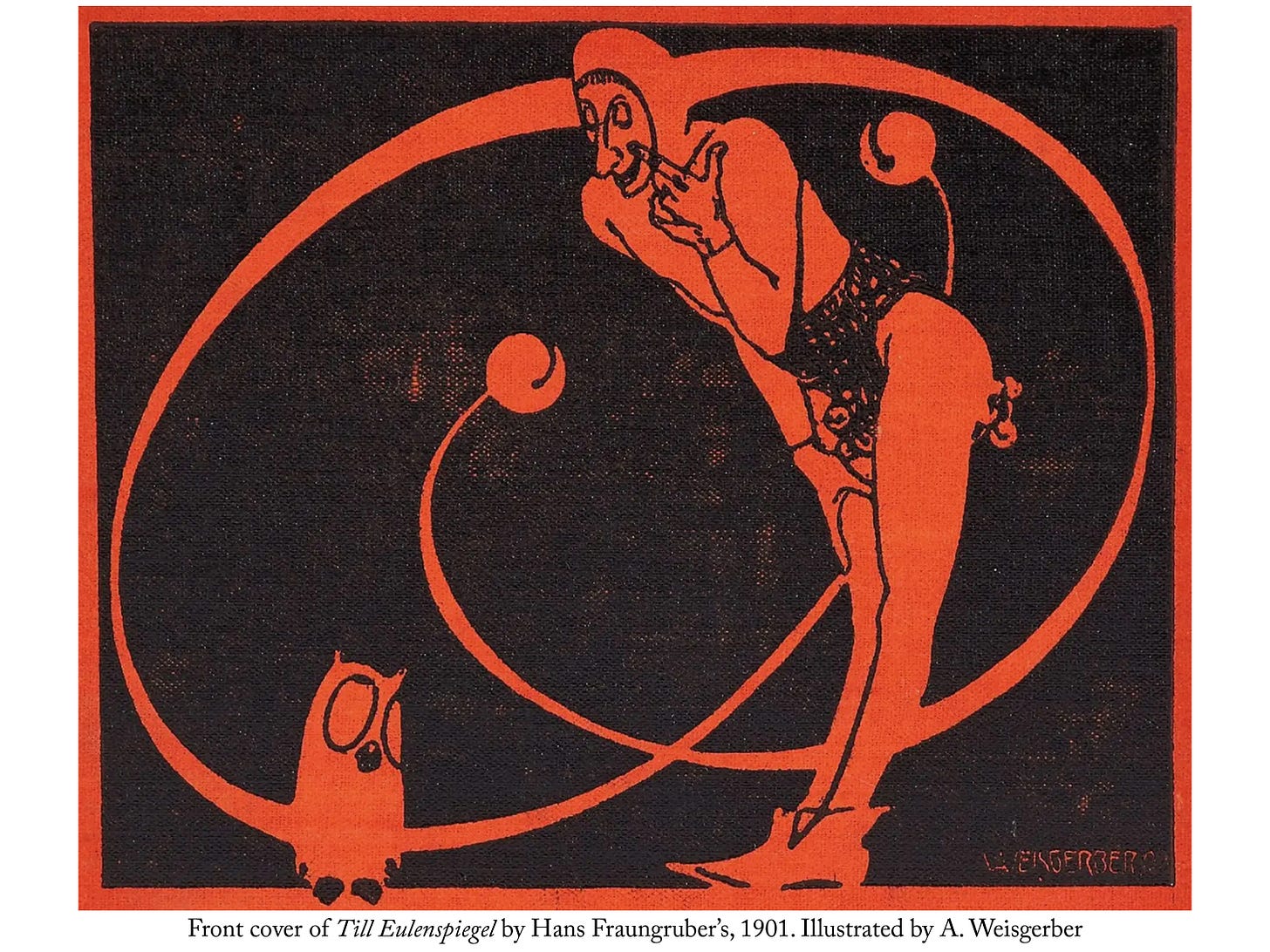

In a similar – but not holy – vein, Germans have enjoyed tales of the simple but cunning peasant prankster Till Eulenspiegel since the fourteenth century. His name translates as Owl-Mirror, which is misleading to modern audiences because owls were seen as symbols of foolishness rather than wisdom in the Middle Ages. It also sounded rather like ‘wipe arse’ in Low German, which would have appealed to the medieval sense of humour. The stories about Eulenspiegel, often scatological, typically expose the greed, hypocrisy or stupidity of townspeople, merchants, clergy, nobility and anyone else giving the peasant a hard time.

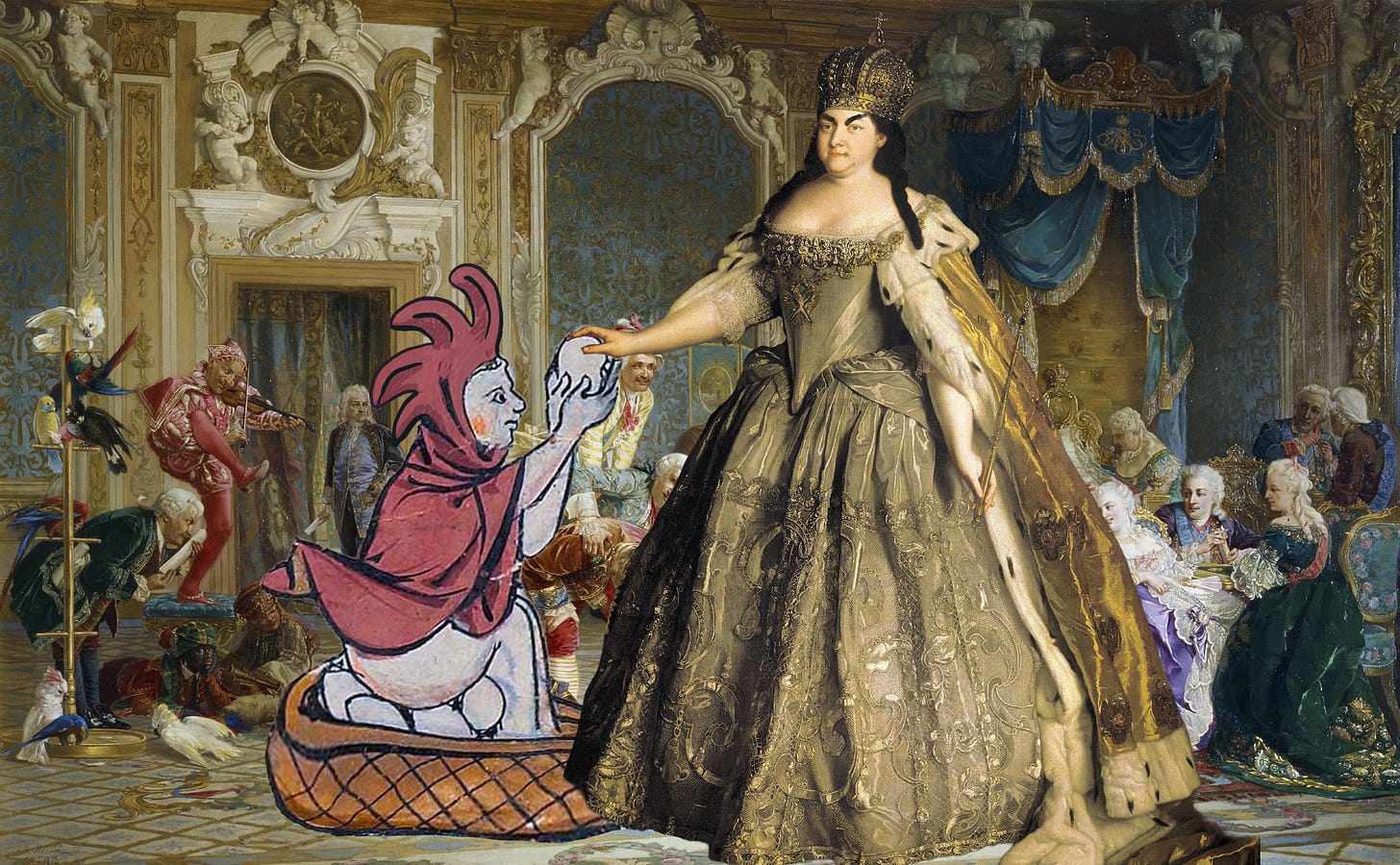

The role of court jester fell into decline in Europe from the seventeenth century onwards, coincidentally and perhaps causally linked with the rise of theatre. Interestingly, it had also declined in China as theatre took off there during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). Russia, however, was slow to abandon the court fool. Jan Da Costa, a Portuguese Jew was engaged by Peter the Great of Russia as a jester from 1714, and did very well for himself, receiving an island in the Baltic for his services. He stayed on to work for three of Peter’s successors, disappearing from history during the reign of the Empress Anna (1730-1740).

Even by Romanoff standards, Anna was one warped autocrat. The historian Simon Sebag Montefiore has likened her to an omnipotent schoolgirl bully. To humiliate or punish them, or just for her own amusement, aristocrats were often relegated to jesters, made to play the fool in her ‘Court of Fools’. Most memorable, perhaps, was one Prince Mikhail Golitsyn, who having been fool enough to enrage the Empress by converting to Catholicism (to marry an Italian), was forced to play at being a chicken, sitting in a basket clucking, and pretending to lay eggs. Not a wise fool, clearly

"This festive tradition appears to have ended with him; at any rate it is not a feature of the Royal Family’s modern Yuletide gatherings at Sandringham." Perhaps a new job for Andrew this coming year.

Really enjoyed this. The distinction between wise fools and natural fools cuts to the core of how power structures need outlets for honesty, even if its packaged as entertainment. Back in college I actually wrote a paper on Shakespeare's use of fools as truth-tellers, and the parallels with modern-day political satire are stronger than most people realzie. When Basil could scold Ivan but ministers got purged, it shows how institutional roles can protect dissent better than individual courage sometimes does.