WORD PLAY: a topic too boundless for the confines of Boundless Play?

Words by Jerome Fletcher

A small child sits on the floor with his mother, hands together, ready to clap in time to her voice as she recites: ‘Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake, baker’s man’. A father runs his finger around his daughter’s chubby palm and recites: ‘Round and round the garden, like a teddy bear...’ Already she is squirming in delight at the prospect of what happens after ‘one step, two steps…’. From a developmental point of view, there is so much going on in these two scenes, but one thing is clear – a strong link between language and play is being established even before we have the capacity to register any memories. Playing and language (language-learning in particular) are so entwined that it may be impossible to talk of one without the other. This is hardly surprising given the now widely-accepted relationship between games and creativity.

In his book, Playing and Reality, the British psychologist D. W. Winnicott makes an explicit link between the notions of play and creativity.

‘… in playing, and perhaps only in playing, the child or adult is free to be creative.’

And this is not a question of idle recreation. Creativity is central to the discovery, or rather the construction, of our innermost identity.

‘… and it is only in being creative that the individual discovers the self.’

This link between creativity and play is further developed by Winnicott in relation to the development of culture, here used in a very broad sense. Thus, he argues:

‘For me, playing leads on naturally to cultural experience and indeed forms its foundation.’

This idea is echoed by Johan Huizinga in his classic book on games and culture, Homo Ludens. He starts from the point of view that playing/games and culture are inextricably linked, expressed in very similar terms to Winnicott.

‘The view we take … is that culture arises in the form of play, that it is played from the very beginning’.

And he specifically talks about the way in which language is a particularly good example of the sort of creative play out of which culture grows:

‘The great archetypal activities of human society are permeated with play from the start. Take language, for instance … In the making of speech and language, the spirit is continually ‘sparking’ between matter and mind, as it were, playing with this wondrous nominative faculty. Behind every abstract expression there lie the boldest of metaphors, and every metaphor is a play upon words.’

So, what we have here is a triad of terms - play, creativity and culture - which are intimately connected, plus a sense that language is a particularly significant element that joins the three of them together. Language is the very important raw material for creativity and is something which is available to almost everybody.

It is easy to see how language and wordplay go hand-in-hand in childhood. But clearly, it is a relationship which is not confined to our early years. Throughout our life, there are any number of games which are specifically based on the playful manipulation of language. Indeed, some such as the early 20th century linguistic philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, argued that Language itself (with a capital ‘L’) is structured like a game and therefore every time we speak or write we are in effect ‘playing a language game’ according to a certain set of rules and structures.

There are myriad examples of cultures manipulating words (in the broadest sense) and the raw material of language in creative, playful, often competitive ways. Given that the topic of ‘word play’ is enormous, probably boundless, Boundless Play will be returning to it many times over the coming months. For now, here is a brief introduction and short guide to the approach we will be taking when writing about ‘word play’ or ‘playing with words’ in subsequent posts.

One place where we might start to further explore this relationship between language and play is with an important distinction. The fact is that we access language in two very different ways - through our eyes and through our ears; written and signed language through our eyes and verbal language through our ears. Not forgetting of course braille where language is taken in tactilely through fingertips.

Words are made up of visible marks on a surface and/or sounds, and although it is generally assumed that the written language is simply a visual equivalent of the spoken, this is far from the case. Here’s an example from James Joyce, delighting in the fact that in English it is possible to spell the word ‘Fish’ as ‘Ghoti’. (/F/ as in touGH, /i/ as in ‘wOmen’ and /sh/ as in ‘acTIon’). In other words, the link between the written and spoken forms of language is not at all straightforward. When it comes to word play then, some ‘games’ are wholly dependent on either the sound qualities or the visual qualities of language. Take the French sentence, ‘Si six scies scient six cyprés, six cent six scies scient six cent six cyprés’. (If six saws saw six cypress trees, six hundred and six saws saw six hundred and six cypress trees). When you hear this spoken, it is a riddle. It sounds simply like 13 repetitions of one word, ‘si’, with a couple of other sounds thrown in. It requires some significant work to make sense of it. When you see/read this in French, the play element is lost. It becomes nothing more than a logical but very uninteresting sentence.

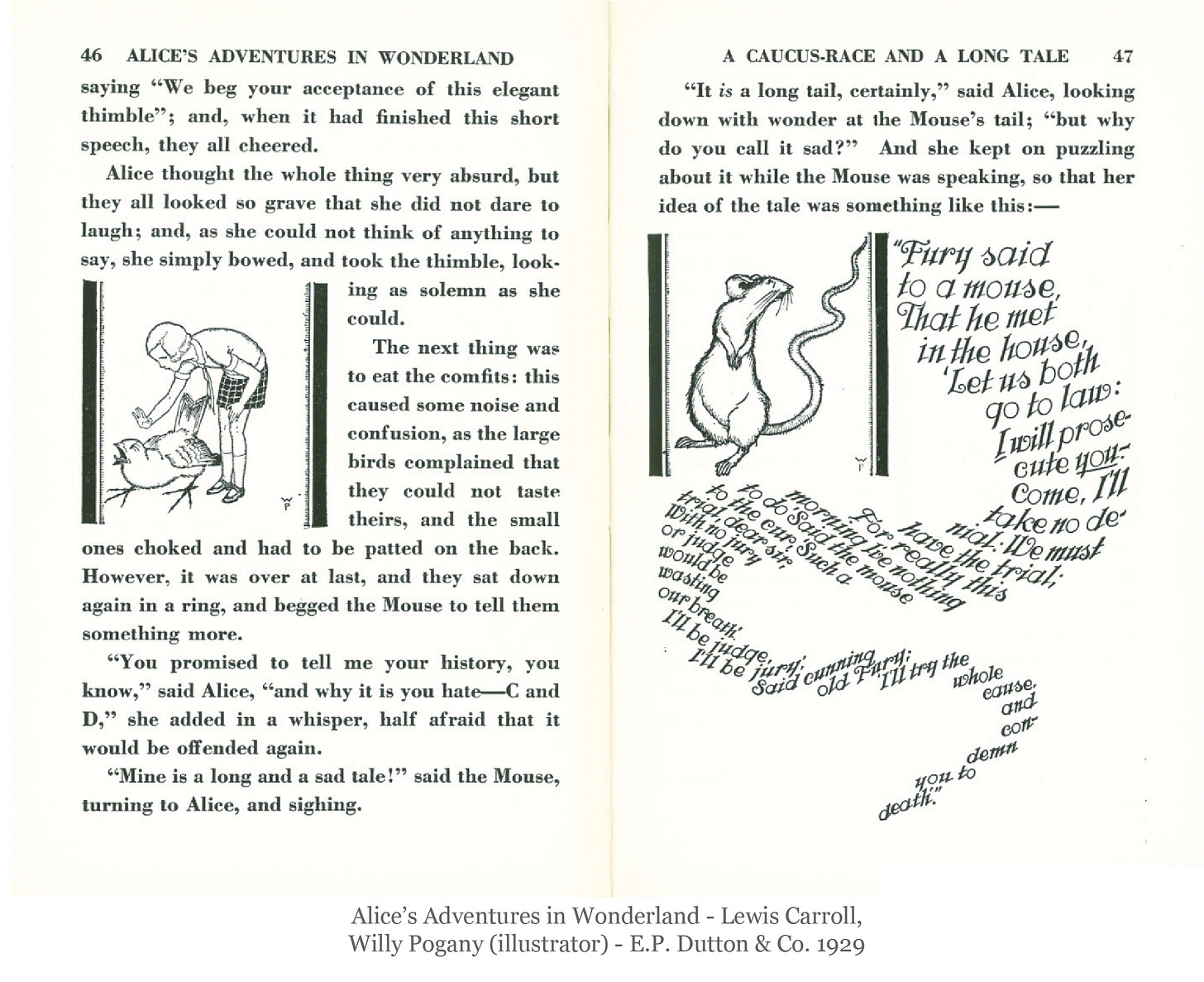

On the other hand, some verbal word games depend largely on the visual aspects of language. A good example would be Lewis Carroll’s poem, the Mouse’s Tail. When you hear this poem read you can’t ‘see’ that it is set out precisely in the shape of a tail. Again, the play element is lost.

Here already we can divide wordplay into two camps, although as ever we will be able to find examples of wordplay which depend on both the visual and the spoken. (The James Joyce example above would be one). And one writing technology that very much muddies the waters is the computer. The digital environment of screen and speakers allows for a whole new range of playful experimentation with words, where the visual and the verbal co-exist and collide.

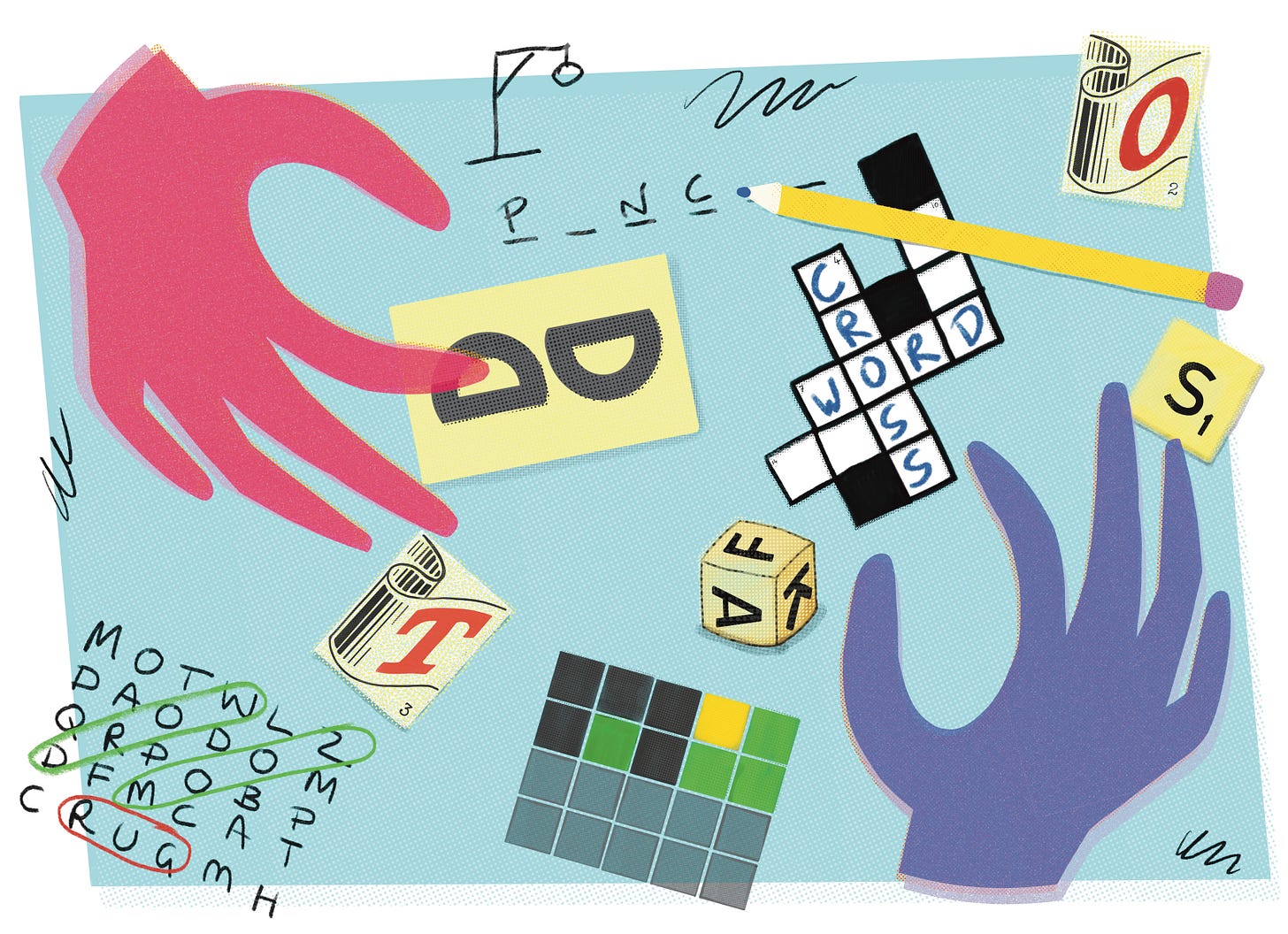

Thus, bearing in mind the above, and given that even Boundless Play has its limits (!), the only way we can hope to present even a small fraction of the whole world of wordplay is by breaking down the subject into three separate posts. Each of these posts will concentrate on one of three main categories: Playing with the written word; Playing with the spoken word and Playing with digital words and language. In addition to this, we will post occasional articles that focus on the more traditional games that involve playing with words (e.g. crossword puzzles, Scrabble, Anagram), albeit always from an unusual perspective.